I See Satan Fall Like Lightning: An Introduction to René Girard's Mimetic Theory

Outline of a talk given to the 2025 Girard Society retreat

What follows below is the introductory talk I recently gave to the Stanford Girard Society at their 2025 retreat. This is meant as an introduction to René Girard’s mimetic theory and its anthropological application to Christianity. We spent significant time after the talk reviewing the core text for the retreat, Girard’s I See Satan Fall Like Lightning.

I noted before kicking off the retreat, and repeatedly afterwards, that Girard’s work should primarily be read as an anthropological theory first, not theology.1 Getting into questions of a “Girardian theology” is beyond the scope of this talk.

A second talk covering Girard’s social implications of Christianity is forthcoming.

Thanks for having me out this weekend. I’m by no means an expert in the work of René Girard, but I have led a number of these discussions on his works over the last decade and hope to be able to make this a fruitful weekend both for all of you as well as, selfishly, for myself. I also hope that this will be, to the extent that we can make a discussion about such an idiosyncratic thinker practical, a weekend that you can take out into the world to critically engage with reality as it is. Girard’s theory, while abstract at first, is ultimately a tool for reading both texts and reality — one that often explains human conflict more powerfully than modern secular theories.

In this short opening talk, I’ll cover some of the basics that we’d glean from reading the core text together, as well as perhaps present a few opportunities for critical engagement with Girard’s work. From there, we’ll move to discussion on the core text. Later today, we’ll take a look at two pieces which take Girardian thought as a jumping-off point for social and financial criticism.

When I was first asked to lead this discussion, we chatted about which work of Girard’s we’d focus on. I settled on I See Satan Fall Like Lightning for a few reasons.

First, a lot of Girard’s work focuses on classics (his first articulation of mimetic desire appears in the lesser-known Deceit, Desire and the Novel, whereas Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World lays out the full system. But I See Satan Fall Like Lightning is, in my opinion, his clearest and most mature synthesis) and it’s hard to assume everybody has familiarity with these texts going into the conversation. I assume everybody here has at least some basic acquaintance with the Gospels, the core focus of I See Satan Fall Like Lightning.

Second, while Girard started as a literary critic and later anthropologist, he more or less came to view all of his work as an apology for Christianity (“On War and Apocalypse,” 2009). No work does this better or more explicitly than I See Satan Fall Like Lightning.

Third, Girard was a prolific writer who published more than two dozen books over a decades-long career in academia. Like anybody writing that long, his thought will evolve and change over time, with the refinement of certain themes, the dropping of others, and the development of broader theories addressing deeper and deeper issues. I See Satan Fall Like Lightning was published in 1999, towards the end of Girard’s academic career, allowing us to engage with his ideas as they’ve fermented and matured over decades.

Fourth, of course, it’s also a short text.

Girard’s project is ambitious and ultimately deeply Christian (though, he claims, not theological). He wants to de-mythologize Christianity.2 He is not looking to dismantle Christianity; rather, he wants to show just how Christianity dismantles the violent sacred. He simultaneously aims to re-sacralize anthropology that has been rendered flat and empty by modernist rationalism, which refuses to take seriously the Christian narrative and holds classic mythology up on a pedestal. This, he ultimately believes, makes the case for why Christianity is the true religion clear to those who are able to see the violence at the core of both ancient mythologies and Christianity itself.

To see how he attempts this, let’s walk through a few things:

Mimetic theory 101

Mimetic theory as foundational to civilization

The Christian Revolution

In our next session, I’ll give a short talk touching on Girard’s idea of hyper-Christianity, the Antichrist, and the Apocalypse. But let’s start with the core of this book.

Mimetic Theory 101

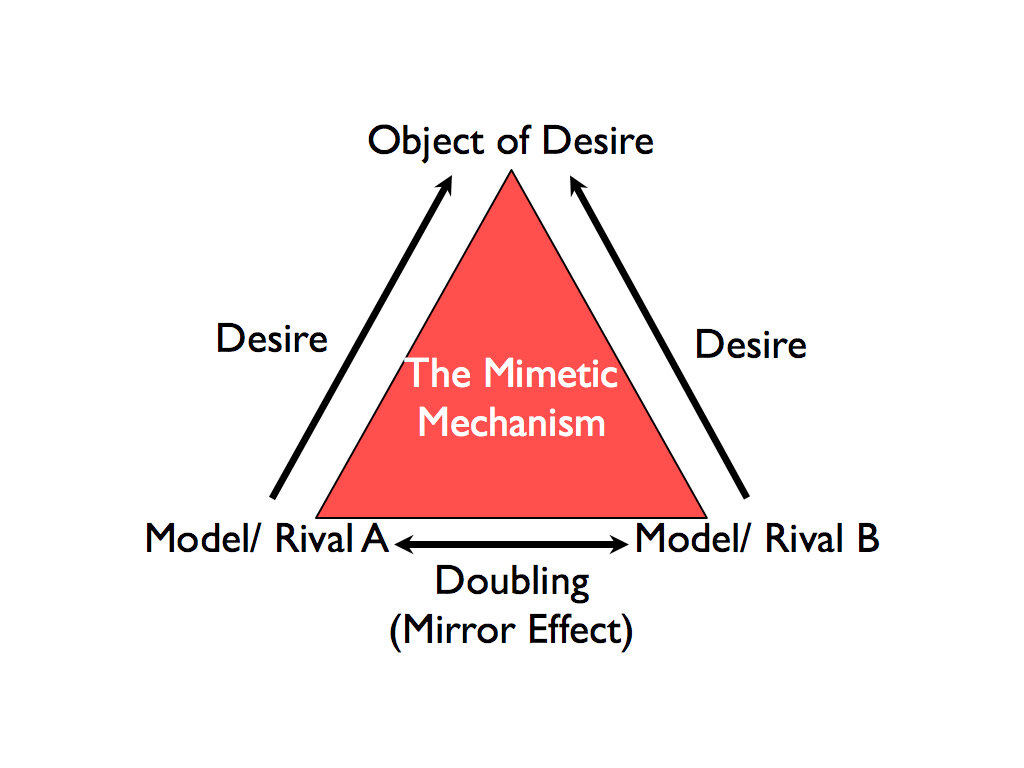

Girard is best known for mimetic theory. The defining characteristic to humans, according to Girard, is desire. We plan for the future, look to acquire goods, prestige, etc. And in doing so, we desire those goods. In desiring those goods, we imitate others. Party A desires (or is thought to desire) Good X. Party B sees that Party A desires Good X and, in seeing Party A’s desire for Good X, Party B comes to desire it more. A becomes a model of desire for B. When the model is near — socially or physically — rivalry escalates.

Girard calls this an internal mediation of desire, which breeds conflict. External mediation occurs when the model is distant (like a literary hero or celebrity), and rivalry is less intense. I want to come back to external mediation later with respect to the role of Christ as one true mediator.

But returning to our example: this desire creates a feedback loop, where now A desires X more, himself (and so B also becomes a Model for A in a real-life society of flesh-and-blood people), and so B desires X even more intensely.

This intensifying desire for the good creates rivalry. And in the process of A and B imitating each other’s desire for X, they become more alike (though they perceive themselves as becoming less-and-less alike). This is the process of mimetic doubling. B is scandalized by A — that is, A becomes both a model and an obstacle. This is what Girard calls skandalon: a stumbling block we can’t stop imitating, even as we grow resentful.3 We hate what we admire, and vice versa.

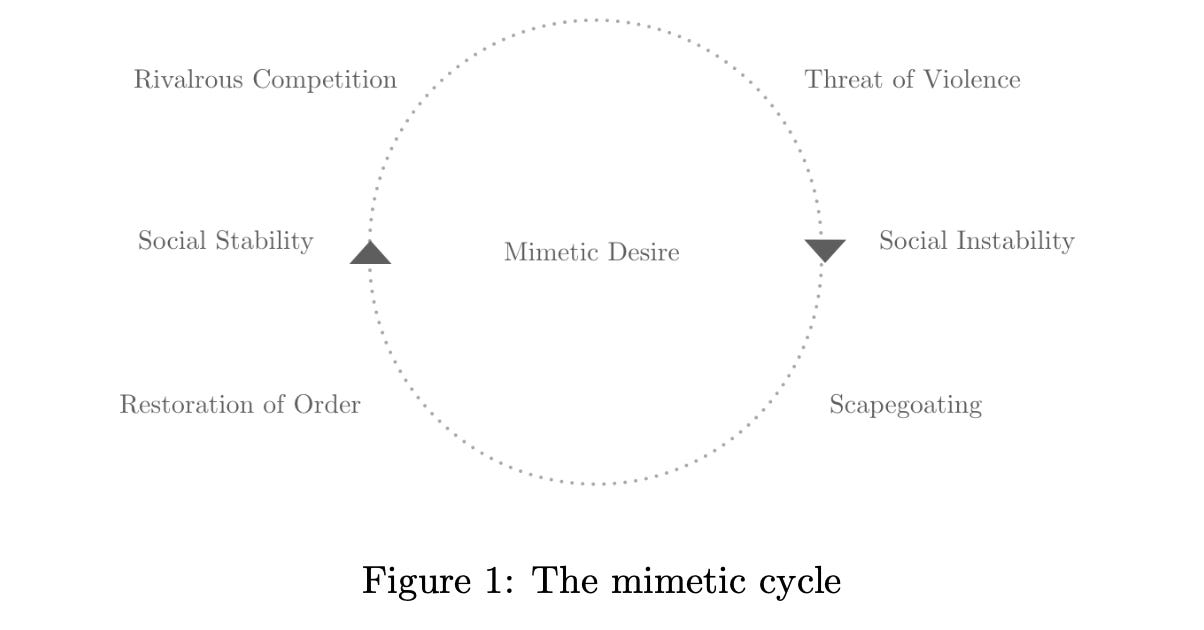

This does not occur in some mere vacuum (except in the cases of twins/close siblings, which are relevant for foundational myths). Others in the society come to desire these rivalrous goods. And as their desire intensifies, so does their rivalry. As the rivalry intensifies, so does their mimetic doubling. Discord and strife break out in the community. Eventually, the mimesis is so strong among members of the community, the doubling so intense, scandal so rife, conformity and rivalry so high, that it must be released in some fashion or the community will tear itself to shreds. The community then “lets off steam,” to take a phrase on which Girard’s translator focuses in the foreword.

How does it do this? By turning on somebody and, often literally, tearing that person to shreds. The community’s mimesis, at a fever pitch, turns into the act of scapegoating a victim. All the blames and frustrations are turned on this person, usually a downtrodden, defenseless type, like a refugee, an immigrant, a beggar, or the sick and disabled. After this victim is scapegoated, usually through being exiled, murdered, or, in the systems of archaic religions (more on this soon), sacrificed, the community “cools off,” and the process starts all over again. Importantly, none of this is deliberate. It’s an unconscious, pre-rational (sub-rational?) process that only becomes ritualized and codified later.

This is the cycle of mimetic violence and it is core to Girard’s understanding of human society. The desire in this process is neither good nor bad, per se. It merely is. He takes mimetic desire as a given. It’s not the desire itself that is bad but rather the violence that comes from it.

Girard identifies this process through antiquity, literature, and mythology. Importantly, in pre-Judeo-Christian society, the victim is always seen as guilty in some way or another. Oedipus is depicted in the myth as guilty of bringing the plague, killing his father, and marrying his mother For Girard, he is not in fact guilty.4 This is a post hoc justification for a communal murder. The beggar stoned to death in Ephesus “is revealed” to have been a demon all along.5 The victims are painted as monstrous and dangerous to the community. This illusion of guilt is essential to the scapegoating mechanism working.

Mimetic Theory and Civilization

Mimetic desire is so fundamental to society, and the violence that results from it so powerful and dangerous, that communities must develop ways to alleviate the threat. Here enters mythology and archaic religion.

After the victim is expelled or killed, peace and tranquility re-enter the community as the mimetic doubling subsides. The members of the community realize this connection – something about the “guilty” victim being killed has brought them peace. They then divinize the victim. This is true, according to Girard, in the founding stories of Rome (Romulus and Remus), Indian mythology (Indra and Vritra), and Greek mythology (Oedipus, Dionysus & later the pharmakos).6

This guilty-into-mythic transformation is what binds these societies together. Rituals of sacrifice eventually arise to keep the mimetic contagion under control and protect the stability of the community. These become what Girard repeatedly calls “archaic religions.” The rites of the pharmakos are an example of this. One of these less-fortunates is chosen, dressed in royal garb, paraded through town and mocked, and eventually either expelled or murdered. The city is “purified” or “cleansed” through this process and, again, peace is restored. If the victim is not seen as guilty, the mechanism wouldn’t work. The crowd would have a significantly harder time turning on the victim, as we see in Ephesus, and the eventual violence would lose much of its cleansing effect as the guilt of the murder falls upon the members of the lynch mob.

As mythologies and historians of antiquity recall these rites, the crowd is portrayed positively and the victim negatively. It is only in Judaism that we begin to see variations on this process. Joseph, Job, the Suffering Servant, and the prophets of Judaism are also all scapegoated but clearly the narrators of the Old Testament view them as righteous, not guilty.7 They are not divinized, as that would be tantamount to idolatry, but it is noteworthy that Judaism, in which we see the first inklings of charity and what later become the corporal acts of mercy, both contains this mimetic cycle and inverts an important element on it. This should hardly be surprising if 1) we take mimetic desire as a given; and 2) we look at the Decalogue, which ends with a commandment against coveting the goods (something rivalrous!) of another. The mythologies of old and the Old Testament, therefore, lay the groundwork for the “Triumph of the Cross” that Girard sees in the Passion.

The Christian Revolution

Having understood all of this, we can quickly see where Girard is going with respect to the Passion. Much like the scapegoats of old, Christ is surrounded by a mimetic frenzy : the crowd turns on Him (yet they “Know not what they do.”), He is beaten, scourged, dressed in mock-regalia, paraded and ridiculed, and ultimately executed in the most humiliating way — a death reserved for the worst criminals of Roman society. And much like the Old Testament prophets, He is innocent. Unlike them, he is divine. He is God. Unlike any victim before or since, He actually resurrects. The disciples spread the Good News to the edges of the Roman Empire. They tell the story of Christ’s Passion, death, and Resurrection. In Girardian terms: they tell the story of the scapegoating mechanism for what it is - an actually divine Person, who was actually innocent, was murdered in the kind of frenzy that at this point defines society.8

This is a total revolution, according to Girard. In Christ’s Passion we begin to see the scapegoating and lynching of every victim before and after Christ, and we see them for what they really are: victims. Christ unites to His Cross the suffering of every victim of the scapegoating mechanism and brings to fore the guilt of all who participate in the scapegoating.

The scapegoat mechanism relies on the illusion that the victim is guilty and monstrous. But if the victim — Christ — is revealed as innocent and divine, then the entire structure collapses. The crowd can no longer hide its violence behind sacred myth. The cathartic power of scapegoating disappears when we see it for what it is: murder. If scapegoating ends in just plain murder when the illusion is stripped away, what power does it really have to hold society together?

None, says Girard. Christianity therefore de-mystifies archaic religion. The rites and sacrifices re-enacting the violence at the core of these mythologies lose their secret, hidden power. He says, in his 2009 essay on Clausewitz’s On War:

[A]ll demystification comes from Christianity. Even better: The only true religion is the one that demystifies archaic religions. Christ came to take the victim’s place. He placed himself at the heart of the system to reveal its hidden workings. The second Adam, to use St. Paul’s expression, revealed to us how the first came to be. The Passion teaches us that humanity results from sacrifice, is born with religion. Only religion has been able to contain the conflicts that would have otherwise destroyed the first groups of humans. Mimetic theory does not seek to demonstrate that myth is null but to shed light on the fundamental discontinuity and continuity between the Passion and archaic religion. Christ’s divinity, which precedes the Crucifixion, introduces a radical rupture from the archaic, but Christ’s resurrection is in complete continuity with all forms of religion that preceded it. The way out of archaic religion comes at this price. A good theory about humanity must be based on a good theory about God.

This Triumph of the Cross undermines the very foundation of archaic society. It reveals the fact that archaic society is built on innocent blood. Scapegoating no longer creates myths and rituals. When it happens, it only happens in a much weaker form.

In embracing the Truth and reality of the scapegoating mechanism, Christianity also brings down what binds these societies together: mimetic violence and scapegoating.

Girard emphasizes early on that “Satan drives out Satan” — meaning the system preserves peace through violence, even though that peace is itself diabolical. Girard is right to note that Satan means “accuser” in Hebrew. 9

He identifies the scandal and violence that culminates in scapegoating with Satan, the father of lies, a liar from the beginning. Indeed, it is Satan that is the driving force behind mimetic contagion, scandal, and violence. Satan, for Girard, is less a metaphysical entity as the name for the accusatory, mimetic logic at the heart of human culture. Satan is the father of the pagan, archaic systems of old that sacrifice innocent victims to bring tranquility to their communities. And it is Satan who drives the crowd to crucify Christ.

This, then, is the Triumph of the Cross. God defeats Satan by revealing his system as the murderous evil that it is. The “powers and principalities” of which St. Paul speaks are, to Girard, not disembodied fallen angels per se but rather the spiritual-temporal pagan states that built their societies on top of this innocent blood.10 And it is the scapegoating mechanism at the core of their spiritual-temporal rule to which St. Paul refers:

For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places. (Ephesians 6:12)

The Christian revolution not only eventually destroys the pagan sacrifice states of old, but it ushers in a social revolution in introducing full-fledged charity: concern for the victim. This concern for the victim is obviously incommensurable with the archaic religions built on scapegoating, as Girard notes, when we know we have a scapegoat, scapegoating loses its power. This concern for victims, now widespread historical fact taken for granted by enlightened modern minds, is itself the fruit of Christianity’s slow transformation of cultural consciousness.

In our next session, we’ll talk about this concern for the victim and some of Girard’s social analysis of modernity. We’ll look at Girard’s belief that we’re not in post-Christianity, or secularism, but rather ultra-Christianity, and that it is ultra-Christianity that lays the foundation for the entrance of the Antichrist and the Apocalypse.

The Canticle of Revelation (11:17-18; 12:10b-12a) has a new dimension with this Girardian analysis. It is this hymn on the judgement of God, common in the hour of Vespers, with which I want to close:

We praise you, the Lord God Almighty,

who is and who was.

You have assumed your great power,

you have begun your reign.

The nations have raged in anger,

but then came your day of wrath

and the moment to judge the dead:

the time to reward your servants the prophets

and the holy ones who revere you,

the great and the small alike.

Now have salvation and power come,

the reign of our God and the authority

of his Anointed One.

For the accuser of our brothers is cast out,

who night and day accused them before God.

They defeated him by the blood of the Lamb

and by the word of their testimony;

love for life did not deter them from death.

So rejoice, you heavens,

and you that dwell therein!

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, Girard, Orbis Books, p. 3. “Since all this knowledge comes from the Gospels, the present book can define itself as a defense of our Judaic and Christian tradition, as an apology of Christianity rooted in what amounts to a Gospel-inspired breakthrough in the field of social science, not of theology.” (Bold emphasis mine.) and ibid. p. 191 - 192, “My research is only indirectly theological, moving as it does across the field of a Gospel anthropology unfortunately neglected by theologians.” Unfortunately, these clarifications don’t really stop Girard from making what definitely-seem-like theological claims in the work. Regardless, I think one way we can read this is that you can take the Christian story as a given and then reason an anthropology that emerges from Christianity.

“On War and Apocalypse,” Girard, First Things, 2009. “This is the implacable logic of the sacred, which myths dissimulate less and less as humans become increasingly self-aware. The decisive point in this evolution is Christian revelation. Rituals had slowly educated humans; after Christianity, they had to do without. Christianity, in other words, demystifies religion.”

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, Girard, Orbis Books, p. 16

ibid. p. 67, 107-115

ibid. Chapter 4, “The Horrible Miracle of Apollonius of Tyana”

ibid. Chapter 7, “The Founding Murder”

ibid. p. 106-115

ibid. p. 139-143

ibid. Chapter 3, “Satan”

ibid. p. 98