Weekend Reads: March 11, 2022

Techno-Optimism?, Renaissance, and the Kingdom of God, Vitamin D, Housing Mania

Hello to all the new subscribers and welcome back to the old subscribers. After a short hiatus at the end of last year, I hope to return to more regular writing here. A combination of personal and professional focuses — plus a general writing fatigue, if I’m being honest — was behind that. But you can expect more regular articles from me as well as more of these “weekend read” posts that include content I’m enjoying over the past week.

Salon Reader: Technology, Renaissance, and the Kingdom of God

I had the opportunity to join students from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute last weekend for a discussion on Towards Heaven or Hell: Technology, Renaissance, and the Kingdom of God. It’s essentially a short seminar/salon discussion on a concept Peter Thiel & co. call definite optimism, with some theological flavors and questions around it. I’m working on a piece or two with some takeaways but here are the readings from this permutation of the workshop:

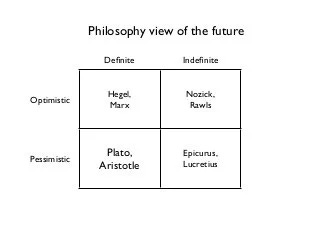

Chapter 6 of Zero to One - “You are Not a Lottery Ticket” - This is the chapter against luck and where the ideas of definite, indefinite, optimistic, and pessimistic frameworks for societies and individuals are presented.

“Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already-invented ones. Bankers make money by rearranging the capital structures of already existing companies. Lawyers resolve disputes over old things or help other people structure their affairs. And private equity investors and management consultants don’t start new businesses; they squeeze extra efficiency from old ones with incessant procedural optimizations. It’s no surprise that these fields all attract disproportionate numbers of high-achieving Ivy League optionality chasers; what could be a more appropriate reward for two decades of résumé-building than a seemingly elite, process-oriented career that promises to “keep options open”?”

“While a definitely optimistic future would need engineers to design underwater cities and settlements in space, an indefinitely optimistic future calls for more bankers and lawyers. Finance epitomizes indefinite thinking because it is the only way to make money when you have no idea how to create wealth. If they don’t go to law school, bright college graduates head to Wall Street precisely because they have no real plan for their careers.”

“Back to the Future,” Thiel - A short piece reviewing Ross Douthat’s The Decadent Society but that lays out the challenge facing Western countries well while briefly.

“Science and technology are natural allies to this Judeo-Western optimism, especially if we remain open to an eschatological frame in which God works through us in building the kingdom of heaven today, here on Earth—in which the kingdom of heaven is both a future reality and something partially achievable in the present. Given a choice, it makes more sense to ally with atheist optimism than with atheist pessimism—and we should remain open to the idea that even Faust’s land-reclamation project is a part of God’s larger plan. After all, in the Bible, the sea is the place where the demon Leviathan lives, and it symbolizes the chaos that must be rolled back. And chaos will be rolled back all the way: “And I saw a new heaven and a new earth . . . and the sea was no more”(Rev 21:1, emphasis added)”

An excerpt from Chapter 3, “Satan,” of Rene Girard’s I See Satan Fall Like Lightning - This is the book I recommend for those interested in learning about Girard 101. While I’ve seen others quick to recommend The Scapegoat or Deceit, Desire & the Novel, this one is short, translated well, and is based on Girard’s interpretation of texts that almost anybody vaguely familiar with the Western Canon should understand: the Gospels. Link here for the whole book.

“If we listen to Satan, who may sound like a very progressive and likeable educator, we may feel initially that we are "liberated," but this impression does not last because Satan deprives us of everything that protects us from rivalistic imitation. Rather than warning us of the trap that awaits us, Satan makes us fall into it. He applauds the idea that prohibitions are of no use and that transgressing them contains no danger.

The road on which Satan starts us is broad and easy; it is the superhighway of mimetic crisis. But then suddenly there appears an unexpected obstacle between us and the object of our desire, and to our consternation, just when we thought we had left Satan far behind us, it is he, or one of his surrogates, who shows up to block the route. This is the first of many transformations of Satan: the seducer of the beginnings is transformed quickly into a forbidding adversary, an opponent more serious than all the prohibitions not yet transgressed.”

“Patriotism” television segment by Ven. Archbishop Fulton Sheen

If I had to do the salon/seminar again, I’d probably split it over a few sessions with the Thiel in one session, the Ven. Abp. Sheen in one session, and a bigger chunk of I See Satan Fall Like Lightning in a separate session.

More on takeaways from this soon, in a separate piece. I figured some readers may enjoy these selections.

Vitamin D: Supervitamin, ad nauseam

Most people do not get enough vitamin D, even those who supplement with it. Chances are this is a significant driver of a lot of un-healthfulness we see from fatigue to infections to mood.

Housing Boom & Bust: All the Devils are Here

Specifically, reading chapters 5, 6, 8, and 9 for an upcoming workshop on mimesis and bubbles hosted by 1517 Fund and run by Byrne Hobart in Austin in a few weeks.

This book is for our section on the mimetic nature of the housing bubble. If you’ve read The Big Short (or even seen the movie adaptation), a lot of what’s here won’t necessarily surprise you. That being said, I’ve found this a better, more detailed history of the crisis.

Here’s one particularly mimetic example:

It was the 2004 holiday season, and a college student—let’s call him Bob—was home in Sacramento. One night, out on the town, he met another young man—Slickdaddy G, Bob nicknamed him. Slickdaddy G, who was twenty-six, was a “larger-than-life personality type,” Bob recalls. “He had perfectly highlighted blond hair, short and gelled, perfect white teeth, perfect bronzed skin.” He also had his own limo driver and a seemingly endless supply of money. Bob joined Slickdaddy G for a night of club hopping, picking up pretty girls and drinking Dom Pérignon. The crew ended up at a penthouse apartment—it was just called “the P”—where an “insane party” was taking place. “A DJ, and more girls, booze, and drugs than you can imagine,” says Bob. “It was one of the crazier experiences of my life to this point.” The next morning, Bob asked Slickdaddy G, “What the hell do you do?”

“Ameriquest” came the reply. “I’m in the mortgage business.”

Incredibly, the subprime mortgage business, which had been left for dead, had come roaring back, bigger than ever. Never mind that most of the mortgage originators during the first subprime bubble—subprime one, let’s call it—had gone bust, or that giving mortgages to shaky borrowers had led to a rather unsurprising rise in foreclosures. And never mind that the subprime financial model had been very nearly discredited. “Subprime one,” says Josh Rosner, “was the petri dish.”

The second subprime bubble was as wild as anything ever seen in American business. During subprime two, kids just out of school—sometimes high school—became loan officers, some of them pulling down $30,000 or $40,000 a month. (Slickdaddy G told Bob that in one especially good month he took home $125,000.) In some places, like Ameriquest’s Sacramento offices, where Bob had taken a job in 2005, drug usage was an open secret, former loan officers say, especially coke and meth, so that the loan officers could sell fourteen hours a day. And the money poured in.It wasn’t just Ameriquest, either. In 2006, at a Washington Mutual retreat for top performers in Maui, employees performed a rap skit called “I Like Big Bucks.” To the tune of “Baby’s Got Back,” the crew rapped:

I like big bucks and I cannot lieYou mortgage brothers can’t deny

That when the dough rolls in like you’re printin’ your own cash

And you gotta make a splash

You just spends

Like it never ends

’Cuz you gotta have that big new Benz.

What triggered subprime two—besides some very short memories—was Alan Greenspan’s decision to push interest rates down to near historic lows during the first few years of the new century to keep the economy from faltering. (He was reacting to the bursting of the Internet bubble.) Low interest rates drove down mortgage rates, making home purchases more attractive while driving up investor demand for yield. And despite the rampant lending abuses that characterized subprime one, the government continued to smile on the subprime phenomenon because of its supposed benefit in helping more Americans buy homes. Naturally, Greenspan held this view. “Where once more marginal applicants would simply have been denied credit, lenders are now able to quite efficiently judge the risk posed by individual applicants and to price that risk accordingly,” he said in April 2005.

But there was another factor as well. Piece by piece, over the course of nearly two decades, a giant money machine had been assembled that depended on subprime mortgages as its raw material. Wall Street needed subprime mortgages that it could package into securitized bonds. And investors around the world wanted Wall Street’s mortgage products because they offered high yields in a low-yield environment. Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, UBS, Deutsche Bank, even Goldman Sachs, which had stayed away from subprime one (too small-fry), moved heavily into the business. By 2005, the securities industry derived $5.16 billion in revenue from underwriting bonds backed by mortgages and related assets, Fox-Pitt Kelton analyst David Trone told Bloomberg. That accounted for a staggering 25 percent of all bond underwriting revenue.— Excerpt from Chapter 9

In a similar vein, here’s a quick read on why the perceived housing mania right now is probably not like 2008. You may see a short-to-medium term slowdown in the increase of mortgage prices but in the long run, we just need to build more housing.

What I’m reading about this weekend:

IgA antibodies

The Go-Go Years (Also as part of the upcoming workshop)

If there’s anything you’ve really enjoyed recently that you’d like to share, feel free to drop it below or reply to this email and let me know.