Notes on *Nuclear War*

Over the weekend, I read Annie Jacobson’s new book Nuclear War: A Scenario (h/t Tyler Cowen).

It’s exactly what it sounds like: a dramatized scenario of a general nuclear war. The book walks through a timeline starting with the launch of the first missile to the (practical) end of the war — 58 minutes later. At risk of spoiling elements of the book: the war is started by North Korea in a “Bolt from the Blue” (surprise) attack against the United States that destroys Washington, D.C. The scenario goes minute-by-minute through the American chain of command’s responses and jumps between them, Russian, North and South Korean, and NATO actors over the next hour.

The North Korean surprise attack culminates in a general nuclear war between the United States + NATO & Russia. There are a few (reasonable) affordances made in the scenario to make it extra bleak (e.g., the US president is whisked away from his command center by Secret Service before being able to phone the Russian president creating important uncertainty about the target of the American response, American interceptor missiles in Alaska fail to hit the North Korean ICBM, etc.)

It’s a quick and well-researched read. Jacobson had access to senior US personnel across the military and intelligence sectors. It’s also disconcerting, as things in this genre tend to be. I recommend it if you’re interested in existential risk, military strategy, or generally apocalyptic genres.

The book has provided me with some fodder for collecting some of my thoughts on nuclear war and nuclear armaments in general. This is mostly a hodgepodge of thoughts at this point and not to be taken as a cohesive argument against nuclear weapons.

Some quick notes from Jacobson’s book.

We are likely at a more dangerous point regarding nuclear war now than since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Some factors she outlines to make this case:

Russia has adopted a “launch on warning” strategy like the United States (the Soviet Union at least publicly professed a strategy of taking the first impacts before responding) quite recently.

Diplomatic relations between the West and Russia are at all-time lows.

North Korea has tested an ICBM capable of reaching the continental United States. They’ve also exhibited their ability to successfully re-enter a warhead from an ICBM.

The United States has no (known) early-launch interception systems for ICBMs near North Korea. One of the designers of the hydrogen bomb encouraged the US to deploy drones over the Yellow Sea to intercept ICBMs in the early stages of launch. The idea was rejected.

Mass media adds to the hysteria and confusion that contributes to the likelihood of uncalled for retaliation.

In order to retaliate against a North Korean attack, American ICBMs would have to fly over Russia.

Deterrence works until it doesn’t. Then the results are catastrophic, no matter the sequence of events or permutations of initiations.

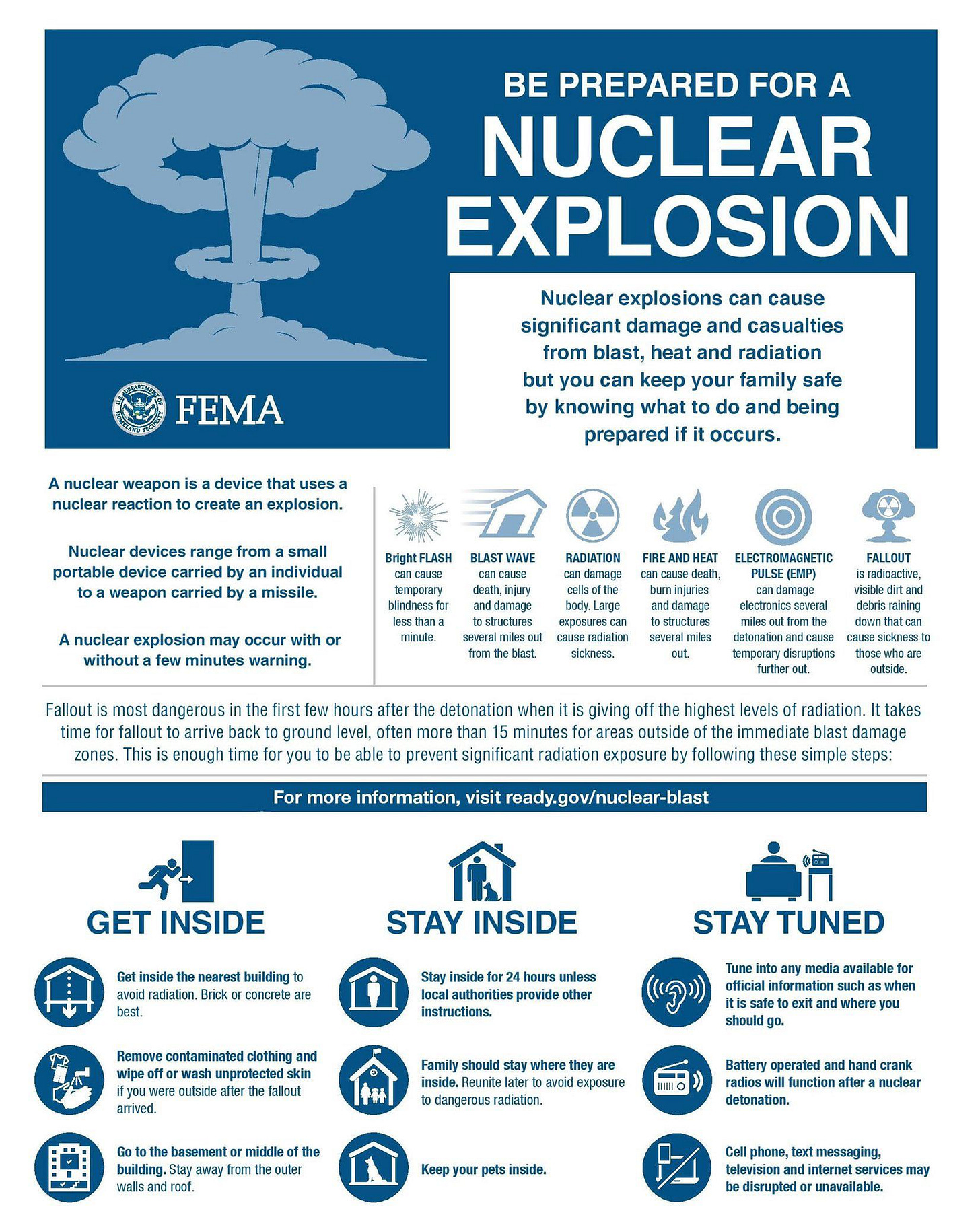

A large scale electromagnetic pulse (EMP) attack on the United States wouldn’t simply mean the electricity goes out and your cars fail to start — it would mean a complete collapse of infrastructure, the destruction of power plants (explosions), chemical plants (chemical fires), hydroelectric dams (flooding). This alone would kill millions.

My general takeaways are:

Underrated:

Diplomacy with the North Koreans (and other “rogue” nuclear powers) and Russians.

Hawkishness towards the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Nuclear non-proliferation efforts.

e.g., at one point there were ~31,000 nuclear warheads stockpiled between the United States and the USSR. There are currently ~3,700 stockpiled between the United States and Russia.

The sheer destruction of any kind of nuclear exchange.

I think we have this popular conception in our mind that nuclear war would be really bad for people on the front-lines and people in major cities. But given the likelihood of any limited exchange becoming a general nuclear war and the effects of fallout, nuclear winter, and EMPs, there’s a good chance any exchange leads to billions (mostly in the Northern Hemisphere) dead from bombs, fires, radiation poisoning, infrastructure collapse, and starvation within the first few weeks.

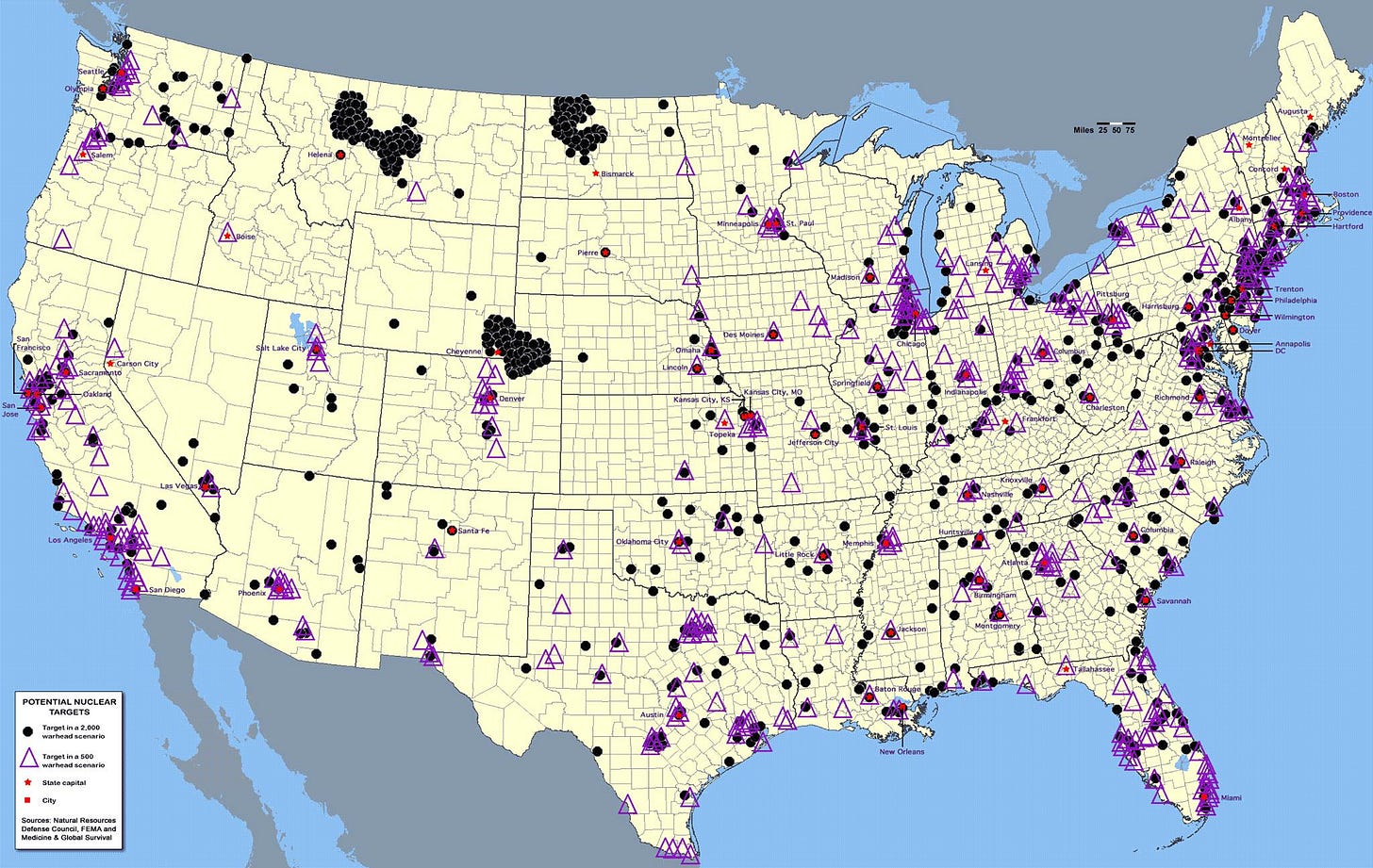

A map sourced from FEMA information showing primary and secondary targets in the United States in a 500 and 2000 warhead nuclear exchange. Note that this map does not show fallout patterns. The risk from AI-generated misinformation

Though not mentioned directly in the book, the way that AI-generated misinformation could contribute to human errors (and the way these human errors play out in the scenario outlined in the book) seems underrated. A lot of AI-risk conversation seems focused on alignment when it should probably be focused on misinformation misleading military and strategic leaders.

Overrated:

Deterrence as a strategy

Existing American interception capabilities

Numerous times throughout the text, experts Jacobson interviews emphasize just how wrong Americans are in believing that their ICBM interception capabilities are good. There are 44 interceptor missiles in Alaska and California. That’s it. And they have a shoddy track-record in controlled tests. Same goes for American missile tracking systems. Satellites can see ICBMs during the launch phase and radars can see later stages of the missiles when they come over the horizon, but in between those two stages, we’re largely blind.

American intelligence capabilities on-the-ground in North Korea

The book focuses on a scenario in North Korea in large part because it would be a “mad king” scenario that makes a “Bolt from the Blue” more believable. The idea that the world could essentially be destroyed based on the whims of a single ruler in a god-king hermit kingdom is honestly so mind-boggling that I’m not sure how one processes it.

Similarly, the book spoke to my priors about nuclear proliferation in general. I’ll likely address these points below at length later, but for now the following bullet points suffice. Arguments for the weapons often include some collection of the following:

“They ended World War II”

This seems really unclear. The Japanese didn’t surrender after the first bomb and knew there were more coming. They had suffered more serious losses during the fire bombing campaigns, anyway. There are compelling arguments that it was the Soviet entry into the war, not the atom bombs, that forced Japanese surrender.

The Japanese figured they could surrender to the Soviets if the Americans invaded from the South and at least preserve a diplomatic, conditional surrender to the war. Soviet entry took that option off the table and meant they’d have to fight a two-front war between a Soviet invasion from the north and an American invasion from the south.

The Japanese surrendering to the Americans and crediting the bombs with the surrender were strategic self-preservation. Such a claim made the Japanese look like victims (after they waged a brutal campaign full of war crimes across the East) and garner sympathy in the post-war trial era. It also served American propaganda interests to claim these innovative American super weapons ended the war.

I also think this is just a purely utilitarian argument, so I don’t find it compelling on philosophical grounds even if it were true. I think it’s totally reasonable to doubt the truth of the claim and demand significantly more proof to make a claim with such staggering negative consequences.

“They ushered in an era of as-yet-unseen peace”

This is only true if you compare wars after World War II to the previous century and if you only compare them to counterfactuals in which you’d have major power conflicts.

An equally compelling claim is that nuclear deterrence raised the cost for direct conflict so much that it made proxy conflicts seem more attractive. Nearly every major armed conflict that has involved a state actor since the proliferation of nuclear weapons has been a proxy conflict between Anglo-American-aligned parties and Soviet/Russian/Chinese-aligned parties. So nuclear deterrence is only “peaceful” for major powers, assuming they don’t end up in a direct conflict.

Most serious nuclear war games between nuclear powers end catastrophically in general nuclear war.

Another counterpoint: there is currently a major power war in Eastern Europe, which should seem unlikely given the deterrence theory.

Finally, nuclear weapons also raise the cost of intervention in defense of another against nuclear-armed powers. If a nuclear power is committing a genocide or ethnically cleansing a neighbor, the best another power can do is strong-armed diplomacy or arming insurgencies. Soviet and Chinese Communism killed ~100 million people in the 20th Century, often under the protective shield of their nuclear capabilities.

“The arms race also ushered in an era of great scientific advancement. Everything from semiconductors and miniaturization to look-down radar, satellites, and the Internet can trace their roots to the arms race.”

It’s hard to weigh the strength of this claim without knowing what the counterfactual reality would look like. Would you have had similar technological advancement at a significantly lower or higher human cost without the arms race? We don’t know. Defense spending certainly is a driver of a lot of technological research and development. What else would this money be spent on without the threat of nuclear annihilation?

It’s worth noting that one of the reasons we don’t have widespread nuclear energy available today is because of the arms race, not the opposite. Midcentury R&D programs went into nuclear research that could also be militarized, with programs focused on less-easily militarized technologies like molten-salt reactors taking a backseat to uranium- and plutonium-fueled reactors that also kill two birds with one stone for military planners.

This is to say nothing of the absolute terror that nuclear war instilled in those who lived under its daily threat. Years ago, I asked a German teacher why the Germans are simultaneously so obsessed with environmentalism but also so terrified of nuclear energy (compared to, say, the French, who historically have a much friendlier — though not perfect — attitude towards nuclear energy). She pointed out that Germany was considered the front-line of the Cold War for decades. In any scenario — limited tactical exchanges or general nuclear war — Germany was probably going to be where the bombs fell. This created a deep-seated fear of anything nuclear.

The one thing that I will give the arms race credit for is that it seemed to usher in an era of entertaining American Cinema about nuclear war, from Dr. Strangelove to WarGames…

I enjoyed your notes Zack. This reflects many of my own thoughts on Nuclear Arms and Nuclear Power. I am an advocate for Nuclear Power and I think one of the great tragedies of the 20th century technology is the lack of follow up on the molten salt reactor and breeder reactors. Our current nuclear energy technology is basically stuck in the 1950’s and much of it is because of an incredibly burdensome regulatory environment which makes private investment prohibitively expensive and risky. Government investment is largely focused on nuclear arms instead of nuclear energy. This is one reason the Milton Salt Reactor was shut down.