Nirvana Fallacy

Compare realistic alternatives against each other, not imagined perfect realities

“You want to homeschool your children? Don’t you worry about them being well-socialized?”

I’ve gotten some version of this question — either directly or as an aside — in about half of all conversations I’ve had about homeschooling. The implicit assumption here — usually unsaid — is that children who attend school are well-socialized (whatever that means). Even under a broad definition of “well-socialized,” this seems like a stretch in most cases. Children in traditional schools interact with people their own ages (+/- 1 year) from their own and nearby ZIP codes. Many are bullied. For many, this is the primary place they will experience violence at the hands of another person. I can go on, but this isn’t a post about homeschooling versus traditional schooling.

The interlocutor here is falling into a nirvana fallacy — they are comparing one alternative (i.e., homeschooling) against an unrealistic status quo (i.e., some world where the average student gets well-socialized in school).

In any conversation about the future, whether that’s a pitch for a new technology, policy discussions, or personal planning, we have to compare at least two choices against each other. Too often, people slide into comparing one alternative to an unrealistic alternative.

This makes discussion about future choices mindbogglingly difficult and unfair. Perfect-sounding counterfactuals can be found for any scenario or proposal, but the only useful counterfactuals are those that come from realistic alternatives. Not to be confused with status quo bias (I’ll probably cover in a future post or conversation), the nirvana fallacy is a function of painting a wonderful counterfactual that doesn’t actually exist. Sometimes this is the status quo, but sometimes this is just an alternative proposal that isn’t actually realistic based on the resources and opportunities currently on the table.

Consider:

“The homeschool sounds great, but aren’t you concerned they won’t be well socialized?”

This compares homeschooling (and a rather negative depiction of it — it’s not like homeschoolers sit in Chinese Rooms getting information slide under the door on pieces of paper from their parents for 12 years and are then released into the world) against an unrealistic (for many) vision of attending school. A fairer consideration here would be comparing what this family would likely be doing at homeschool with what kind of schooling environment this child would likely be subjected to. Unless the family is particularly well off or in an outstanding school district, the homeschooling option likely comes out ahead on the socialization front.

“Space exploration sounds interesting, but shouldn’t we be spending money on taking care of the planet here?”

This kind of line comes about any time there’s serious conversation about colonizing Mars, building a Moon base, or just generally making humanity a multi-planetary species. Often, it’s accompanied by the implication that companies like SpaceX shouldn’t be spending their resources on, well, space, and rather be giving that money to causes like alleviating homelessness and charity.

Those are good and admirable causes, of course, but it’s not like SpaceX can just overnight turn their facilities into homeless shelters, fire their staff, hire unpaid volunteers, and give their money to charity. A more insidious insinuation is often that the company should be so heavily taxed that it can’t do space exploration and that money should be spent on welfare causes. This seems to particularly fall into a nirvana fallacy. Where is this reality where the taxing-entity (usually the US government, but possibly the CA government) is actually skilled and adept at solving homelessness or other welfare problems? Where is the proposal alongside this conversation that it is merely a function of not having enough money (and that that money can be had from space exploration companies), so the solution must be seizing the assets of the few billionaires actually pushing for multi-generational technological leaps?

This would be a better objection if the question really were “space or charity?” But that’s not the question at hand. That’s an unrealistic alternative.

“Sure, you could start your own charter city, but aren’t you concerned the rich and powerful would take over?”

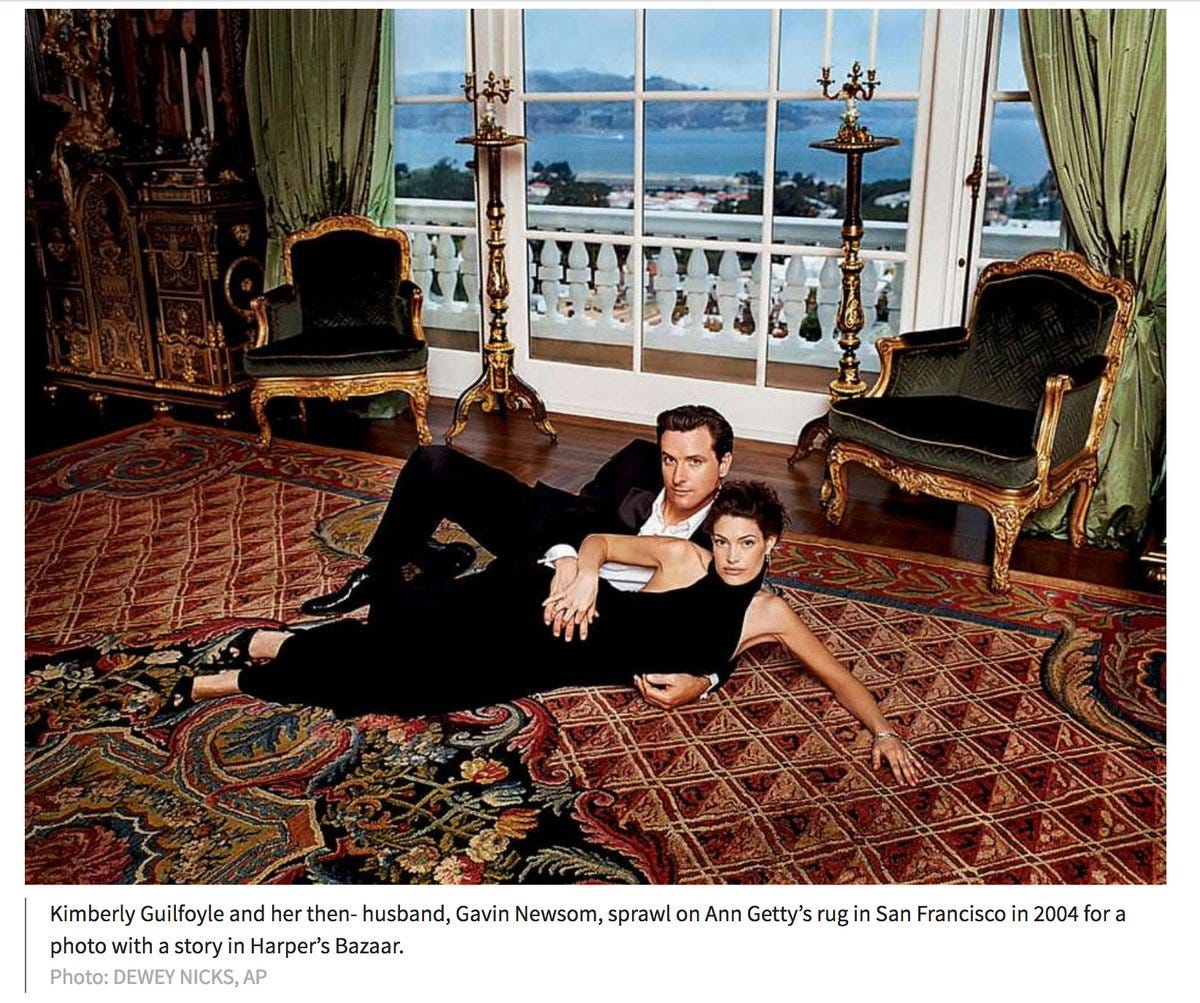

I’ve heard some version of this come up from well-intentioned friends who fear that charter cities will just be playgrounds for the rich and powerful. My response to them would be simple: look around. Political machines have existed in cities since time immemorial (you can read of the machinations of Ancient Israel in the Old Testament) and American cities are particularly affected. Heck, California is run by a Patrick Bateman-lookalike who got rich owning businesses like wineries, was appointed into politics by a corrupt mayor, and who takes bizarre photos laying on expensive rugs in lavish mansions in the most expensive neighborhood in northern California. That isn’t a place run by the rich and powerful?

To me, the point of recognizing the nirvana fallacy is to make clear just how much better things could really be if we tried. It’s too easy to nay-say by painting up realities that don’t exist or by airbrushing the current world to make it seem like things are actually pretty okay.

(Yes, it’s possible for the nirvana fallacy to go the other way — but I think this is not that big of a problem. Pitches and visions should be realistic and there are plenty of people who will push back against unrealistic pitches.)

When you compare realistic alternatives to each other, the world opens up. There are so many matrices upon which we can improve.

Maybe you see that schools actually are quite bad at socialization, so you set out to make it easier to get children into better educational environments that will help them flourish as well-socialized adults in the future. Perhaps you see just how much the rich and powerful — whether cartoonish governors or power-hungry zoning boards — control existing institutions, so you’re more inspired to go out and make it easier to build outside of their grasp. Maybe you just get better at ignoring the nay-sayers who throw peanuts from the stands to make you feel bad about not working on their pet issues when you’ve set out to build a company, a family, or a career of your own.

In any comparison, remember to compare realistic alternatives against each other.