New Things Anew: Pope Leo, Rerum Novarum, and Catholic Social Teaching

An overview of the popes speaking to the modern world

The following is part of a conference I gave to a Catholic young adults group, introducing the papal teachings on Catholic Social Teaching. Not included below is a significant portion of time on Q/A related to topics like economics, development of theological teaching, and specific questions related to the content of the mentioned encyclicals.

I’d like to thank the organizers for inviting me this evening. I am hardly an expert on this topic, but I do hope it’s a fruitful evening together, as I’ve become interested in this topic when I realized I really had soul in the game here.

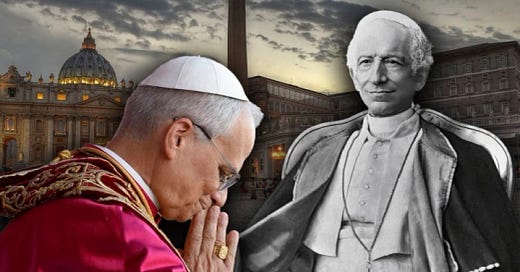

We had initially discussed this several months ago and settled on this date. Of course we had no clue that it would be particularly relevant this week. Not only has the newly-elected Holy Father taken the name Leo XIV – Leo XIII being the pontiff typically associated with the institution of Catholic Social Teaching and the author of Rerum Novarum – but Leo XIV explicitly noted after his election that he was inspired to take the name in part because of the influence of Rerum Novarum:

"... I chose to take the name Leo XIV. There are different reasons for this, but mainly because Pope Leo XIII in his historic Encyclical Rerum Novarum addressed the social question in the context of the first great industrial revolution. In our own day, the Church offers to everyone the treasury of her social teaching in response to another industrial revolution and to developments in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges for the defence of human dignity, justice and labour."

Yesterday was also the 134th anniversary of Rerum Novarum and, based on hints already dropped by Leo XIV, I expect we’ll see lots of citations to this document and developments on it in this pontificate. Even this morning, Pope Leo XIV affirmed the importance of the family as a society, using language reminiscent of Leo XIII’s anthropology in Rerum Novarum.

So what I want to do for you today is explore the importance of Rerum Novarum, the context in which Leo XIII was writing, how we can understand this context with respect to the Church generally and to the Church today, and give you some principles from Catholic Social Teaching that we see both in Rerum Novarum but as well as other magisterial documents since Rerum Novarum. What I hope for you to take from this is an understanding of what Catholic Social Teaching is, how it is different from the ideologies that dominate our world today, and how the Church can and does speak to the world. I also hope that this will provide you with a grounding to understand and engage with the social teaching that we’ll see from the new Holy Father.

The encyclical itself is rather short and readable, so we’re not going to dig into a paragraph-by-paragraph summary or derivation of specific arguments. If you haven’t read it yet, I encourage you to do so. It’s also important to note that this is hardly Leo XIII’s only social encyclical. As pope, he wrote 86 encyclicals in 25 years, including Diuturnum Illud and Immortale Dei on the origin of political power, Libertas condemning the liberal conception of liberty and asserting the Christian conception, Sapientiae Christianae on the duties of Christian citizens, Longinqua Oceani on the challenges and opportunities for the Church in the United States, and Testem Benevolentiae on Americanism. To get a fuller view of the tradition, I encourage you to read beyond Rerum Novarum.

RERUM NOVARUM AND CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING - EVER ANCIENT AND EVER NEW

You sometimes hear it said that Rerum Novarum introduced Catholic Social Teaching, or that Leo XIII introduced Catholic Social Teaching. In a certain sense this is true, but it's also not true. It's true in the sense that the thing that we call Catholic Social Teaching is inaugurated with this encyclical, that you see the Church speaking to the world in a way that touches on many temporal issues of economics, justice, and politics, in a way in this document that you don't see said in previous documents. But it's also not true that it's something totally new or totally invented in 1891. Just a quick look at the citations in the document can show you this. Pope Leo XIII pulls from St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church Fathers, and a long tradition of talking to temporal and social issues in the world. He’s not inventing something new - but he’s speaking in a new way to the world based on the context and challenges of the world in 1891.

It’s helpful to look at the context of the document to understand its importance and influence. “Rerum Novarum” translates literally as “New Things,” and colloquially as “On Revolutions.”

These “new things” in the 19th century are legion. Technology, social institutions, governments, the state of the Church in the world, and the practical beliefs of large masses of people are totally different at this point than they were even a century before. Vatican I, the first ecumenical council since Trent in the 16th Century, had only recently concluded and drew specific lines around papal infallibility. Liberalism and socialism are in full-swing and Christianity is, at this point, privatized enough that the temporal powers largely don’t even think about consulting the Papacy about how they want to run their governments. This is tragic in one sense but also provides a new opportunity for the Church to speak up on temporal matters.

Leo XIII sees, rightfully, that we have gone from a world in which the Church is the world to a world in which the Church sits, in a certain sense, apart from the world. For the first time since the collapse of the Roman Empire, it can be said that the Church really sits as a shining city on a hill (to pull language from Pope Leo XIV) rather than diffused throughout society broadly, and therefore can exert teaching authority in a way that is not immediately seen as a threat by the temporal powers.

In short, we enter into post-Christianity. Pope Leo XIII recognizes the burden under which the masses toil after the advent of the Industrial Revolution. He also sees the ideologies that have popped up to fill the void left by Christianity throughout society. These ideologies are, and continue to this day to be, some form of socialism and liberalism.

Liberalism gives rise to the conditions under which the industrial revolution is possible. And then the conditions of the industrial revolution give rise to socialism as a response to those crushing conditions for the working masses.

Leo XIII acknowledges the attraction for many of these ideologies. And with this encyclical he tells the world that they have to accept neither socialism nor liberalism. Instead, he says, Christianity and Christian society are the answers to the social strife that gives rise to ideologies.

He strikes at the heart of socialism by declaring unequivocally that a right to private property exists and that man has this right to promote his temporal and spiritual good. But he also strikes at liberalism by asserting the dignity of the worker and subverts liberalism by noting just how poorly the liberal order actually preserves private property and the ownership of productive assets by those doing the work.

He exhorts political leaders to protect the dignity of the worker, the right to private property and well-ordered enterprise, and respect for the right moral order in society. And he also teaches the Christian worker to go forth into society and do the work of building up a Christian civil society.

CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING IS NEITHER SOCIALIST NOR LIBERAL

It is a mistake to read this document as either pro-socialist or pro-liberal. The Pope is, to use language from Pius XI in his social encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, steering the ship of the Church (and, exhorting society to follow the Church) between the twin rocks of liberalism and socialism. Liberalism is bad and denies the dignity of the worker, the true nature of man, society, and freedom. Socialism is worse and deeply unjust. The solution is to reach back into the tradition and pull the lessons from Christendom, from the Angelic Doctor, and the Church Fathers.

The socialists say there is no (or extremely limited) right to private property. The Church says no, private property is a natural right given by God to man to till the earth and fill it. He uses this right to provide for himself, his family, and the poor.

The liberals say that property belongs to individuals who exert their labor over it. The Church says no, property exists for the good of all and private property exists to serve that end. (This is known as the Universal Destination of Goods, a core principle of Catholic Social Teaching.)

The socialists say that society is fundamentally made up of classes of labor and capital, that these classes are in natural conflict, and that the hierarchy found in them is unjust. The Church says no, society fundamentally is made up of man in relation to God and of families that precede the state. Hierarchy is natural and, when ordered properly, a good thing.

The liberals say that political authority comes from the people. The Church says no, political authority comes from God.

The socialists say that the state ought to manage the relations among workers and between workers and capital. The Church says no, a community of higher order should not interfere in the life of a community of lower order. (This is the principle of subsidiarity.)

The liberals say that wages should purely be a function of free agreement between two individuals and that there’s no such thing as an unjust wage so long as it was freely agreed upon. The Church says no, just wages are a function of being able to pay a worker a rate that would allow him to frugally support a family.

The socialists say that society is a struggle of class against class. The Church says no, the rich and the poor are one in Christ and can work with and serve each other fruitfully and justly. (This is the principle of solidarity.)

The liberals say that the state ought not prioritize any one type of person against another. The Church says no, the poor are uniquely disadvantaged relative to the rich and that a preferential option ought to be given to them when thinking about policy, constitutional order, and justice. (This is the principle of the preferential option for the poor.)

And both liberals and socialists say that productive assets should be owned by either capital or by labor. But the Church says no, both can own productive assets and these assets ought to be distributed throughout society, so that man can provide for himself and others.

And we could go on. I give these examples to exhort you not to fall into the trap of thinking that Catholic Social Teaching is some kind of way to make socialism or liberalism palatable or to throw a crucifix on something fundamentally post-Christian or anti-Christian.

Catholic Social Teaching, inspired by Leo XIII and developed by popes since him, is radical in comparison to the ideologies of liberalism, individualism, and capitalism, and the ideologies of socialism and communism. It’s a totally different way of seeing society and one that asserts that a Christian order is fundamentally different than the post-Christian, materialist order. There is dignity in work, the rich and the poor can work together without needlessly being at each other’s throats, yet the rich have special duties of charity and justice to the poor, and the State ought to protect the dignity of man in his work, enterprise, and relations.

That fundamental difference is rooted in the fact that the Church sees reality for what it is. Man exists in relationship to God, to a family, and then into a series of other relations like civil society and the State. He is not merely a member of a class struggling against another class or an individual like Robinson Crusoe birthed from the ether onto an island.

This view of reality allows the Church to step into the social order and to guide it according to principles that transcend partisan political debates and ideological struggles. She sees the true purpose and end for man and society, and therefore she can provide principles about the proper purpose of material wealth, enterprise, and political power.

CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING SINCE LEO XIII

Since Leo XIII led the Church in speaking to the modern world, popes continue to build on this with their own new social encyclicals. As times change and new things arise posing challenges to the Church, the dignity of the human person, and the temporal order’s relationship to the spiritual, new popes take up this mantle to show how the Church can lead the world and avoid catastrophe in materialism and ideology.

While each pope has his share of social encyclicals, three encyclicals in particular build off of Rerum Novarum, explicitly and in particular. Those are Quadragesimo Anno by Pius XI, and Laborem Exercens and Centesimus Annus by John Paul II.

Pius XI promulgated Quadragesimo Anno in 1931, forty years after Rerum Novarum, to commemorate Rerum Novarum, clarify the teaching of Leo XIII, and apply it anew to a world in which nationalism, communism, and what the Pope calls “economic dictatorship” are all on the scene. Like Leo XIII before him, Pius XI notes that the Church certainly has authority to speak on temporal matters, even if it may not be her charism to speak on the minutiae of policy.

Pius XI reminds us that while we have a right to private property, that right exists for an end and that end is our sanctification. Failure to use that right properly does not invalidate the right outright, but possession of goods does imply obligations on those who have them. The rich are obligated to support the poor, businessmen ought to invest in their businesses building real things in order to provide meaningful work and pay to their employees, and, importantly, opportunities to become owners. To me, as somebody often on the “capital” side of these conversations, the exhortation of the popes to give workers a chance to share in ownership as a function of their labor is some of the most interesting from the Magisterium. Pius XI encourages the development of partnership-contracts that give workers a share in ownership as a function of their labor. This can take many forms, but arrangements which move towards the vision of private property and labor laid out in Rerum Novarum are to be preferred over mere wages or mere salaries. He also encourages, again, that those doing work and those doing businesses take this mantle out into the workplace and the world, that they bring the Gospel to their coworkers and employees, and that they be “apostles to those who follow industry and trade.”

At the 90th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, John Paul II promulgated Laborem Exercens. Again, context is useful here. We’re looking at a different society in 1981 than in 1931 or 1891. There’s the rule of Communism over much of the globe, financialized capitalism over the rest, mass media, mass migration, and the nature of labor continues to change. John Paul II reminds the Church and the world of the dignity of labor and the laborer, the theological roots of labor (I strongly encourage you to read this document to get a good sense of why the Church views labor as good and dignified, from a theological perspective), and, like Pius XI, applies the principles of Catholic Social Teaching to the “new things” of his age. Just as the family precedes the State, so does labor precede capital, he notes. And from this, we are reminded that man has primacy over things. The new materialism of the Post-War period presents a temptation to view man as subject to the things produced in an economy and he wants to push back on this. Building on Pius XI and Leo XIII before him, he exhorts us to find new opportunities for ownership of productive assets, whether through partnerships, shareholding by workers, or other innovations on business based on the teaching of the Magisterium.

And ten years later, John Paul II then promulgated Centesimus Annus, on the 100th anniversary of Rerum Novarum. Much like Quadragesimo Anno, this document repeats the principles of Rerum Novarum, provides clarification, and applies these principles to the new things of 1991. He condemns fascism, socialism, liberation theology, atheism, consumerism, and the new challenges of mass drug use and pornography. Like much of his writing, John Paul II emphasizes the role of freedom in truth, the way consumerism subjugates the person, and the need for Christians to destroy structures of sin in society through the development of new opportunities, intermediary groups, and organizations rooted in the Gospel and providence. To invest, John Paul II notes, is always a moral choice, “the decision to invest, that is, to offer people an opportunity to make good use of their own labor, is also determined by an attitude of human sympathy and trust in Providence, which reveal the human quality of the person making such decisions.”

NEW THINGS AGAIN

With this rich tradition in view, we begin to get a sense for how a pope like Pope Leo XIV may tackle the new challenges of our time. Clearly things have changed significantly since Rerum Novarum was first promulgated in 1891, but also keep in mind that Centesimus Annus was promulgated nearly 40 years ago and before any significant advances in information technology. The Holy Father explicitly wants to tackle the challenges that artificial intelligence poses to how we think about human dignity, justice, and labor. I’d venture to say that there are other parallels to 1891, 1931, 1981, and 1991, each in their own way. Communism and socialism, at least as they were initially conceived, have largely fallen by the wayside. Liberalism emerged victorious from the Cold War and dropped any remaining pretenses of being the religious-friendly political order.

In terms of technology, mass media no longer means newspapers, radio, and television but instead means every man, woman, and child having access to read and write to every other person on the planet in their pocket at any given time (and this is to say nothing about what generative AI does to media). Pornography is totally mainstream in most western countries. Developing countries are just now coming online. Biotechnology presents both chances to apply our God-given reason in a way to alleviate the suffering of billions, or the temptation to open up a bottomless bottle of Blackpills in an economy of flesh. Advances in robotics will soon reshape the common man’s experience of transportation, agriculture, and warfare. Educators already must be adept to the new challenges (and opportunities) posed by artificial intelligence tools in the hands of students as young as pre-K.

So, there’s a lot to cover. Lots of opportunity for the Church to be a beacon of light to a world now so far from Christendom.

Personally, I am excited about this new pontificate and the Holy Father’s desire to reach back into the rich tradition of the Church and bring it into our times. I pray for him and his cross he must carry in his office, and you should too. We’ll need his leadership.

I’d like to leave you with a quotation from Centesimus Annus that I think sums up Catholic Social Teaching well:

What Sacred Scripture teaches us about the prospects of the Kingdom of God is not without consequences for the life of temporal societies, which, as the adjective indicates, belong to the realm of time, with all that this implies of imperfection and impermanence. The Kingdom of God, being in the world without being of the world, throws light on the order of human society, while the power of grace penetrates that order and gives it life. In this way the requirements of a society worthy of man are better perceived, deviations are corrected, the courage to work for what is good is reinforced. In union with all people of good will, Christians, especially the laity, are called to this task of imbuing human realities with the Gospel. (Centesimus Annus, 25)

Further Resources

The following resources are by no means exhaustive but a good place to start for better understanding Catholic Social Teaching.

Encyclicals:

A Reader in Catholic Social Teaching, ed. Kwasniewski

This book provides a decent foundation but also is lacking in important ways. I would include the following not found in the volume:

Laborem Exercens by Pope John Paul II

Podcast: “Pope Leo: Rerum Novarum and Catholic Social Teaching on the 134th anniversary,” Andrew Willard Jones & Alex Denley

Published on May 15, 2025, this podcast provides helpful context, some of which is covered in this talk, for understanding Rerum Novarum. I highly recommend Andrew Willard Jones’ work on Church history.

Thanks to Rev. Canon Ross Bourgeois, I.C., for helping workshop an earlier version of this talk.