Adventure Capitalism 03

The Two (or Three) Keys to Helping Young Professionals Build a Future; How to Work Remotely; Job Opportunities; Resource Update

Welcome to issue 03 of Adventure Capitalism. This issue includes elements from issue 02.0, plus a few resources I came across over the holiday that you may enjoy. I originally planned this to be 02.1, but then the essays included became long enough that I decided this would become its own standalone issue.

Thanks for your patience in between editions. I was putting the finishing touches on a new podcast for work (here, Founders First, exploring the real, human stories behind starting a business).

You can expect more regular programming going forward.

Follow Up: Eternal Adolescence, Part II: The Fix(es) — I am in the camp that most young adults actually want to grow up but that doing so is harder than pundits think. Limited affordable housing, limited dating market opportunity, and lack of clear, good role models who aren’t harping on them “when I was a kid, I was married and owned a home with three kids by 22!” makes it hard for them to see a straight path forward. Here are some fixes that can make growing up easier.

How To: Work Remotely — I have been blessed for most of my career to be able to work remotely. This has been a huge boon to me and I have worked with a number of people to build this perk into their own careers. Here’s how I do it.

Job Opportunities: Open positions from dozens of companies across the United States and Canada.

Recommended Resource Update: Micro-Acquisitions

What’s coming up next: What to expect in the next issue of Adventure Capitalism.

Eternal Adolescence, Part II: The Fix(es)

In part I of “Eternal Adolescence,” I talked about why so many of America’s coastal elite hubs seem to incentivize putting off growing up. It’s a complex dynamic that has society-shaking repercussions between lowering home ownership rates, fertility rates, startup rates, and general happiness. I also worry that it introduces a dangerous dynamic where you have young people transferring wealth to older people via rent and building controls (i.e., young people pay thousands every month to older landlords, who can charge higher rents because they keep the quantity supplied of housing fixed while demand skyrockets).

But I’m never one to simply complain without trying to offer solutions — and trying to offer solutions that I have SEEN work elsewhere.

Like any complex problem, one simple policy proposal or change in how people think is not going to fix everything. But, piece-by-piece, reform-by-reform, individual-by-individual, we can turn the tide back from this intergenerational reverse-Robinhood and create a better future where people can have families, have great careers, start businesses, and enjoy their communities.

If you’re a young adult who wants to grow up, to start a family, and to begin building that legacy that generations before were able to do more easily, you can do it. It just might take some creativity on the personal level. You can then move this over to the societal level.

I’m going to address this problem as a broad societal problem first. So we’ll take a look at a theory of social change, the elements that go into social change, and then how individual actors (maybe even you, reading this now!) can take action in their own lives to start that social change.

Some Potential Solutions

Complex social change ultimately comes down to a trichotomy cycle: ideas, institutions, and individuals.

Ideas influence institutions which shape individuals and their actions. Ideas and culture are the product of spontaneous order among individuals. Spontaneous orders are the products of individual action but not of individual design. This is why it’s so difficult to design a culture in a family or a company, let alone a society at large. But individuals can change their behaviors and slowly but surely shift the ideas that influence the institutions.

A few individuals — those who are willing to go against the grain — can influence the ideas of a society, shape those institutions, and bring in more individuals who share their ideas. That’s how communities and subcultures create their own social change (see the example of the SSPX at St. Marys). At some point in scale, this moves from subcultural change to broader social change.

We currently live in a social order where the ideas, institutions/incentives, and individuals clash. The ideas, institutions, and individuals of the old social order (e.g., the Baby Boomers) were built by the previous generation (e.g., the Greatest Generation and the Silents) and set up the previous generation for success. These ideas and institutions stayed in place and grew further until they eventually hit a limit.

If you fix housing costs, the cost of medical care, and the cost of education, Americans would easily be the richest people in the world. Young Americans need to know that building or buying a home, having babies, and educating their families won’t destroy them financially or psychologically for decades to come. Fixing these three issues for current and upcoming generations will be the issue to solve Eternal Adolescence.

Let’s take the first issue, housing, as an example.

Under the old regime (the Boomers, who inherited the model from their parents), suburbanization was the answer to housing costs.

Building suburbs leads to cheaper homes for most people so long as transportation speeds increase and land remains abundant. As soon as transportation speeds stagnate (as they have in the United States), it’s more important to be within commuting distance of urban cores where the jobs are. Nobody cares how nice a suburb is if it is 4 hours from work or lacks decent transportation to make that long commute bearable.

(Don’t believe me? Look at home costs in Northeastern Pennsylvania and compare them to the Hudson Valley in New York. Distance-wise, NE PA is not much further from Manhattan than some parts of the Hudson Valley. The Hudson Valley has direct transit into NYC, though, while NE PA does not. Commuting distance matters.)

One approach to fixing this problem would be to change building codes and build up. Instead of pushing people into the suburbs and exurbs, you could keep people in the urban cores and let them live in apartments and condos. This is the core idea behind the YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard) movement in San Francisco, which is trying to make SF more affordable by building taller, denser buildings.

But that runs into institutional challenges. The ideas have yet to trickle down to the institutions, where existing property owners don’t want to lose property value and introduce a lot more people into the neighborhoods where they lived. This might change in time, as these property owners retire or the city becomes so terrible and disgusting that they have to relent. But that assumes that the idea that denser housing will alleviate social ills wins out.

Maybe the YIMBYs will win. But even if they do, YIMBYism only addresses the housing cost issue for a small portion of young Americans living in San Francisco. There are still millions of us living in other cities who still find home ownership inaccessible because of the next issue: education.

If you live in a not-insane city (i.e., not San Francisco), decent homeownership is still out of reach for a lot of young people because property values are a function of public schooling. The same home in two different school districts can have vastly different prices. That’s because Americans place such a high value on school ratings and public schools are assigned by ZIP code. To send your child to a mediocre public school is to condemn them to getting into a mediocre college (or worse, violence in the school), and that, Americans believe, is tantamount to failing as a parent.

(In my own city, you can buy a decent $150,000 home in many parts of the city, but your school district will be the failing city schools. The same home in an affluent suburb with a top-tier public school will run $500,000+. That’s despite the fact that the suburb has lower walkability, fewer overall amenities, and a longer commute time.)

The idea that quality of school determines lifetime outcomes dominates the institution of housing prices and parenting decisions. Young people see that and see $$$$ associated with settling down and having kids. And that totally disregards the costs of medical care to have kids and the insane insurance premiums for a family.

Activist movements like YIMBYism and the School Choice movement may lower these costs (I’m more optimistic about school choice), but young Americans who want to start families and grow up shouldn’t have to pin their hopes and dreams on the success of a few fringe movements. They also shouldn’t have to hope that things change as they grow older and the likelihood that they ever meet their own grandchildren decreases with every passing year.

There’s another set of changes on the individual level that young Americans can take to grow up. Those both involve work and education.

Reform 1: Work Remotely

The first change is the individual decision to work remotely. This suggestion should come as no surprise to my regular readers who know that I am a huge proponent of this for the vast majority of workers.

Unless you work in an industry that actually requires your flesh and bones presence to complete your job at a very specific place, there is no reason why the vast majority of people working in high cost of living places can’t relocate to lower cost of living places. Cities like Austin, Denver, Vegas, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Detroit, and Atlanta have many of the amenities that people want from major cities with a fraction of the price point. As more individuals and families make the decision to relocate to these cities, they bring amenities with them (Austin is a great example here, where the biggest downside of people moving in has been traffic; but the city continues to create new, interesting art, food, and culture as more people move there).

If you already live in a city like these but want to have space and land to start and raise a family, working remotely allows you to live beyond the commutable suburbs in the country, where you can afford to develop your own land. This way, you can still live near the urban center where culture and friends may keep you bound, but you can still acquire land without having to give up weeks every month to moving.

(Yes, I realize not everybody wants the trade-off of moving to a mid-market city or moving to the country, but this is a considerably better fit for most people than they think. Even the exodus from San Francisco to Los Angeles is this on a smaller scale — people will trade off the density of SF for the quality of life in sprawling LA. Visit a few cities and see what you like. Who knows, maybe Tulsa is a great place for your tastes and goals.

Trade-offs certainly exist, but that’s why its important to take an index of what you value. I am reminded of an acquaintance who built a beautiful house on a plot of land in his early 30s. He can afford to do this because property in this region is relatively cheap. He’s embraced the trade-off of slightly diminished career opportunities in order to be in a place he likes and near his family. That trade-off is worth it for him. Many competent young people have had careerism so deeply engrained in their minds from a young age that they haven’t had a chance to ask themselves if they may value provincialism more.)

Thankfully, I see more work trending in this direction, especially as employers have to compete in an increasingly tight labor market. More on this in an essay below.

Reform 2: “Home”school

Working remotely opens up more opportunities to address the question of housing but what about education? Who cares if you can live anywhere if all the places you can afford to live still have abysmal public schools?

But what if you can bypass the failing public schools and exorbitantly expensive private schools altogether?

You can, you just have to be creative.

As I’ve written over on my main blog, when most people hear “homeschooling,” they think about 8 kids loaded into a church van going to churn butter at 5 AM. Either that, or they think about rich families hiring tutors to take care of their kids during the day.

Sure, both things exist, but there’s a huge swath of options in between, many of which barely look like “home”schooling.

Cooperatives are one such alternative/blend, where parents send their kids to a community of other kids. Here, they may learn from an instructor, play with other kids, or go on field trips with chaperones. So, essentially community schooling. Without all the perils of teachers’ unions or sky-high tuitions or mandatory classes or the cops showing up if the parents don’t send their kids.

As more people gain the freedom to work from home, you’ll see more and more of these cooperative blends pop up. There’s already a huge surge of these across most cities in the United States. Some are based around church communities (one friend told me, “this is essentially what traditionalist Catholic families do already”), others are based around interests (another friend send me a list of cooperatives in the Atlanta area sorted by interest and topic).

Legally, the parents sending their children to these cooperatives are “homeschooling,” but they are effectively building up a civil society of other parents, educators, and resources for educating the next generation. At a fraction of the cost of an expensive private school or a 30-year mortgage and property taxes in an expensive school district.

A worthwhile venture may be to make this even easier for aspiring parents. This could mean making it easier for parents to connect with other parents on an ad hoc basis or to bring skilled educators into the home or co-op as the children require education that neither the parents nor the curriculum can provide effectively.

I am long homeschooling and long remote work.

Reform 3(?): Health Shares

Fixing housing and education would take the vast majority of the burden off of the cost of growing up. But it still leaves a big cost, especially a cost that can have a Black Swan effect of coming out of nowhere randomly: health costs.

One approach I have seen that can significantly defray costs for a family is a health share or health ministry. These are essentially membership programs where families pay a monthly fee to join and can request reimbursement for medical costs and procedures, up to a certain amount. While the program can deny reimbursement requests, they practically never do. This works as a sort of quasi-insurance for members who may use it in addition to health insurance (e.g., maybe they have a mediocre employer-offered plan and want additional security) or in lieu of health insurance.

These programs have been around for decades — in fact, they are what health insurance should look like — but blew up after the Affordable Care Act was passed. Most are run as a “health ministry” and have a religious affiliation requirement to join. This allowed individuals who were uninsured to avoid the Individual Mandate penalty under Obamacare to still get “coverage” for their health needs.

I’m generally less familiar with the health insurance and healthcare markets so my commentary here is limited. I am generally optimistic about health share programs as the cost of health insurance continues to climb in the United States.

Individuals Shape Ideas Which Shape Institutions

Like I said above, maybe movements like YIMBYism or School Choice or whatever their radical left wing variants look like will succeed. Maybe they’ll rush in a huge set of institutional changes that will allow more people to own homes, start families, educate their children, and build intergenerational legacies. Maybe the ideas will shift, maybe the institutions will shift with them. I’m not sure. I don’t like making broad predictions outside of the areas I know well and think about often.

But an individual who wants to start a family shouldn’t have to hold their breath for changing institutions or ideas. They should be able actually take action now to start this process of growing up.

Working remotely, homeschooling, or both are great ways to chip away at the big barriers preventing most young Americans from getting started in growing up.

Entrepreneurs and founders who help them do this will not only address a serious and growing market need but they will also contribute to one of the most important issues of our time: making it easier for people to start families.

How to: Work Remotely

Convince your boss to let you work from home; negotiate remote work in a job offer; let your employees work remotely

I’ve had the good fortune to work remotely for most of my career thus far. Save a few weeks where I was expected to show up in the office, I have been able to work where I want, when I want, so long as I accomplish the goals of my role and meet my duties.

This has not only allowed me to live where I want and travel — fine and good consumer goods that I don’t take for granted — it’s also allowed me to think more flexibly about my future than my friends who find themselves chained to a few cities where their company has their offices. And that’s to say nothing of the advantage of being able to avoid office politics, being pulled into superfluous meetings many offices have, and the drudgery of commuting.

If you’re an information-sector worker, a marketer, a salesperson, or anybody who does mot of their work through an email inbox, a word processor, a terminal, or phone lines, you, too, can work remotely.

I’ve made a push with my friends and career coaching advisees to have people work remotely. If not entirely remotely, then they can at least work remotely a few days every week.

If you’re on the job hunt or considering working remotely, I urge you to make it a request in your next negotiation or quarterly review. There are a few things currently working in your favor:

The job market is currently incredibly tight. Companies will go to war over quality talent; this is especially true if the place where your company’s office is is an expensive city with a low quality of life (e.g., Washington, D.C., SF, etc.). If the managers want to keep quality talent and it’s hard to replace that talent, they’ll budge on issues they previously hadn’t considered.

Tech tools have finally come to a place where remote work isn’t a hassle. Tools like Slack, Zoom, and Loom make it easier to communicate with people across the country than it is to walk down the hall and ask a colleague a question.

Employers are aware of the trends and pressures I mentioned in Eternal Adolescence and know it isn’t easy to just uproot yourself and go buy a new house or find a new apartment in a crowded, expensive metro.

What this all means is that the relative cost of allowing people to work remotely is coming down while the relative gains are increasing. Savvy employers know this already and allow their employees to work from home at least part of the time. Not-savvy employers will learn this the hard way when they find it increasingly difficult to compete for decent talent. No company wants to hire sub-par talent.

So, if you haven’t had the chance the work remotely before but want to try your hand at negotiating it, now’s the time to get started.

How to Negotiate with a New Job Offer

When applying for a new job, don’t automatically assume that you have to be in the office every day. Unless the job posting uses the language like, “you’ll be expected to be on-site” or some similar verbiage, you can probably negotiate at least a few days every week of working from home.

(If a job posting does insist on being in the office and the job doesn’t require you to be in the office, consider that a huge red flag of micromanagement.)

When you go through the application process, don’t tell the company from the get-go that you’ll insist on working remotely; that’s something that you will use as a leverage point in your later-stage conversations with them. Make yourself a competitive candidate that the company wants to fight to hire and then make it clear to them that you’ll take the offer if it meets certain criteria that you want.

This is not unlike a home or car purchase negotiation. In those negotiations, you enter in making it clear that you are looking for certain things (e.g., in a car negotiation, you’re looking for a sedan that’s used, has a warranty, and is AWD). Those are your must-haves. You give them a low-anchored price range and they go from there. Once you come up on your price and they come down on theirs, you try to get them to throw in other perks that make the deal worthwhile. You don’t start by offering them your final-offer price. You work up to it.

Similarly here, you want to go in letting them know what kind of work you want to do and what your compensation range looks like (anchor them high; use comp data from places like Salary.com to make sure you aren’t entirely out of left-field).

Once you get the verbal offer, you can make clear that you’ll want to work from home at least part of the time.

You’ll know how much of a concession this is on the company’s part by asking a question during the interview process, “what does your work-from-home policy look like?” If the company tells you people regularly work from home, this is not a big concession. If the company tells you senior employees work from home (and you are applying for a junior position), this will be a bigger concession but one you should try to get them to give you regardless.

A Quick Aside: The Overton Window of Hiring Managers

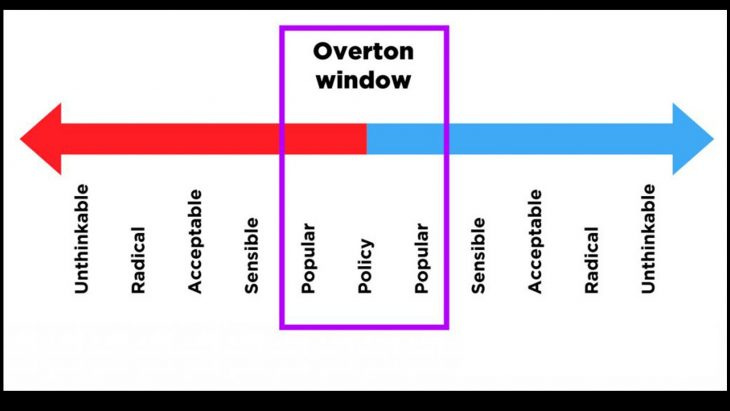

In policy discussions, the Overton Window is a conceptual tool to help illustrate what lawmakers and voters are likely to consider from a “menu of options.”

If Option A is “in the middle of his Overton Window,” and Option B is “at the end of his Overton Window,” that means that, for the voter or lawmaker in question, Option B is somewhat fringey but they would be willing to get on board with it. If Option C is “outside of his Overton Window,” then he won’t even consider it. The Overton Window shifts over time and it is the job of social change (like that proposed in the above essay) to shift the Overton Window to new options.

Just like lawmakers and voters, companies and hiring managers have Overton Windows. If the hiring manager has never let a new hire work from home but may consider it, working from home is on the edge of her Overton Window. Just because something may sound fringey to a company or hiring manager doesn’t mean you shouldn’t ask for that thing. Asking for what’s on the edge of the Overton Window is how you shift it.

Any hiring manager worth their salt will know this is part of the negotiation process. So long as you don’t approach it in an entitled or deceptive way, they’ll consider the possibility.

As with any negotiation, expect there to be a give-and-take. Go into the negotiation with your priorities straight. Are you willing to slide a little on comp in exchange for working remotely (if so, your comp should still be market rate, do not let the company under-pay you based on where you’ll live)? Know what you want out of the offer before getting too deep. That will give you an idea of how to negotiate along the way.

Recommended Book: The Secrets of Power Negotiating

To quickly recap:

Know what you want out of the job offer before going in.

Make yourself a compelling candidate. Make the company want to fight for you.

Prime them for the remote work conversation in the Q/A period at the end of the interview.

Negotiate; do your homework beforehand on comp and company norms.

Be willing to walk away; know what you won’t compromise on.

Different companies will have different norms within their Overton Window with respect to remote work. Highly corporate companies that have a strong meeting culture may be more comfortable with 1-2 days from home, plus working from offices in different cities.

(I have a career coaching client who just took a job offer at one such company. He has high comp and the ability to work from most major US cities because the company has offices in most of them. 100% remote work is currently outside of the company’s Overton Window. He may be able to get there by pushing his managers on the edges of their Overton Windows.)

How to Start Working Remotely in Your Job

Okay, we’ve seen how you can set the stage for a successful remote work negotiation on a new job, but what about if you enjoy your job but just want to work from home?

Just like with hiring managers, every manager has their own Overton Window. If working 100% in the office one week is firmly in the middle of the Window and working 100% remotely the next is outside of the Window, you’ll want to shift your manager over time.

How can you do this?

I attended a workshop on hiring, training, and managing virtual assistants hosted by Ramit Sethi a few years ago. During that workshop, Sethi said something that has stuck with me with respect to any kind of management practice:

Trust is earned.

Now, he was referring to things like giving your VA access to your email inbox or your bank account, but the concept applies across the board.

Managers don’t allow employees to work remotely not because of some ideological opposition to remote work. They don’t allow them to work remotely because of a lack of trust.

This lack of trust can be both lack of trust in the employee to get stuff done and lack of trust in themselves to be a quality manager of a remote team. In my experience, the latter is more common than the former.

That means that you have to build up their trust in you to do your job well and trust in themselves to be your manager while you work remotely.

Trust is earned, so build it up in small chunks. Come out of a strong quarterly review with the request to work from home one day every week, or one morning every week. Then, in the next quarterly review, make the request to move the amount of time spent working from home upwards. Make it clear that you’re not just competent at working from home but you are actually more productive than if you were in the office.

Don’t use retroactive language here (or in any negotiation!). So, don’t say, “I did such a good job with X, I should be able to work remotely now.” Instead, use prospective language, making it clear you’ll be better at your job working from home. “I’d like to work remotely one day every week in the next quarter. I think I can get a lot more done from home and stay on top of everything here in the office by doing that. How can we make this happen?”

If your manager is resistant here, be willing to ask for a trial period.

Take initiative to use tools that make it easier for your manager or your boss to do their job of managing you. Tools like Loom, JIRA/Trello/Basecamp, Zoom, Slack, Toggl, etc. help them stay on top of your work without micromanaging you.

This will require some managing upwards on your part. That’s okay. Be patient with your manager and understand that a big part of your responsibility in taking on remote work is making working with you easier.

I’ve seen managers go from being skeptical of a remote employee to letting their entire team work remotely in as little as two quarters. A big part of getting managers on board with this is just showing them that, no, the company won’t fall apart if you don’t make everybody come in to a physical office every day.

Job Opportunities

I’ve recently updated a list of 100+ job opportunities at startups across North America. There are jobs in:

Austin

Denver

SF Bay Area

LA

NYC

Chicago

Orlando

Waterloo

Barcelona

And remote positions!

You can view the list below. Please forward to any friends who may be looking for work.

Resource Update: Micro-Acquisitions

In a previous issue, I recommended Ryan Kulp’s course Micro-Acquisitions for anybody interested in buying, growing, and selling a small business. Since I last recommended it, a few additional resources have come out with the course, including:

A mini-course on how to hire and manage software developers

Leveraged Buy Out in 60 minutes

Sales growth course

Growth marketing course

Plus, his team built a platform for finding and doing diligence on small businesses you may want to consider buying.

I’m a big fan of Ryan’s stuff. He’s no fake-guru, so if you’re interested, check it out.

Up Next

Upcoming in a future issue of Adventure Capitalism

I will be logging off of social media for Lent, so I hope to send a few shorter issues during the Lenten season as a way of getting my fill of valuable writing.

Essay: The Looming Boomer Baby Business Bust — The median age of business ownership across the United States is on the older end. Younger Boomers and older Gen-X’ers own most businesses, especially those that employ multiple people, with fewer and fewer obvious heirs. What happens when they want to retire but they have no family to pass the business on to?

Essay: In the Presence of the Saints: What Secular Society Loses When We Stop Venerating Saintly Figures — I was recently in Italy, where I saw a number of sculptures and frescos devoted to the lives of the Saints of the Catholic faith. That had me thinking about the role of veneration, of sainthood, and what that means for us as individuals in our personal lives, even outside of the religious connotations and meanings. I think there’s a ton we lose when we lose the idea of trying to live as a saint and the mortification that comes with it.

Essay: Title TBD - Reflections on what Lent means in a culture devoid of penitential acts.

Essay: Who Wants a Billion Dollars Anyway? In Defense of the Lifestyle Business — Based on a recent conversation I’ve had with somebody who knows business ecosystems in cities inside and out, we have to ask, why are cities so intent on building “the next Silicon Valley” when the vast, vast majority of people can’t have that and, honestly, don’t want it? What’s wrong with being a place known for outstanding businesses that pay the bills and provide a great quality of life to their founders and employees?

How to: Know When to Call It Quits

How to: Write a Decent Resume and Never Have to Worry About it Again