Adventure Capitalism 01.0

Real Life Isn't Shark Tank; why trying to change the world makes everything around you worse; you don't have to start a company to be an entrepreneur

You have a real life if and only if you do not compete with anyone in any of your pursuits.

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Welcome to issue 01.0 of Adventure Capitalism.

(Quick note on issue nomenclature. I expect most issues to be longer-form essays like this one. But I may occasionally send shorter issues that may not warrant something this long but still should be read and is relevant for subscribers. Those will be marked as tenths, e.g., 01.1, 01.2, 01.3… think of this as the “Edition X, Issue 12” kind of nomenclature a lot of magazines used to use.")

In this issue:

Essay: Why local investors often drive economic growth to the Bay Area and New York (and how to break the cycle)

Essay: How smart people focusing on “changing the world” inadvertently make everything around them worse (and what they can learn from Heartland Americans)

Recommended Product

Fascinating Job (& Company)

Recommended Twitter Follow

Recommended Reading

“I’m Going to Make You an Offer”

Real Life Isn’t Shark Tank: Who invests in what is a function of that region’s last economic boom.

I’m sitting at a Starbucks in a Heartland city waiting to meet a founder. She started a venture-backed company that raised money both locally and from investors working with one of the best accelerators in the world. She joins me only after I down an entire Grande coffee and the caffeine hits my bloodstream.

The conversation wanders from what it took to sign their biggest enterprise client, to how loose lips sink ships (a major tech publication reported on a deal before it was done and it blew up), to local investors. This is a trip-wire, apparently.

She tells me that she’s raising a few million dollars on a post-money valuation cap a little over $10 million.

“That’s actually quite reasonable, especially for a company that’s come out of that accelerator and has the traction you have.”

“I know. So I was pitching a firm and they had another investor join the meeting. I thought we were pretty far outside of this other investor’s wheelhouse, but whatever, I figured. Anyway, at the end of the pitch, he sits back and tells me, ‘I’m going to make you an offer.’”

“Oh no…”

“Oh yes. So this guy offers to invest $500k for 51% of the company.”

“What.”

“Yes.”

“You raised previously on SAFEs, right? So that would mean that you would own a negative amount in your own company!”

“Correct. He did not understand how SAFEs, let alone convertible notes, worked. Needless to say, I did not take his ‘offer.’”

——

Real life isn’t Shark Tank. Entrepreneurs don’t go up to a board, make a flashy pitch, and wait for investors to come back with equity offers, revenue-sharing agreements, and whatever else you see Kevin O’Leary throw at people on television.

In real life, entrepreneurs usually raise based on a type of debt that later converts into equity, so investors don’t even know how much equity exactly they will own until a later “priced” round. Investors rarely own more than 10% of a company early on because they know that founders need to be properly incentivized to keep working and raise more money down the line.

Here’s the thing about this story: it gets to part of the core issue why so much economic growth (especially on paper) goes to coastal hubs like San Francisco, San Jose, and New York City. Even though you’ll see more companies start outside of these exorbitantly expensive hubs — like my friend’s company above — you’ll see them eventually have to go to these hubs to raise money if investors can’t learn how to play by the rules of the market.

If Heartland cities want to compete with the coasts for high-growth, high-margin technology companies — and the jobs they bring with them — then they need to find a place for every type of investor in the ecosystem.

This means not just lumping every rich person in the category of “tech angel investor.” And it means helping those who do want to be tech angel investors change and adapt to new financial tools, mechanisms, and expectations that develop over time.

A region’s investor-base is usually a function of whatever that region’s most recent economic boom was. If that boom didn’t include tech financing, don’t expect the moneymen in the region to know the ins-and-outs of tech financing.

For example, here are some of the archetypes I’ve found in cities that haven’t had a big tech boom since the Dot Com Bubble:

The Professional, MBA, JD, MD - This is a high-income professional like a doctor or a lawyer who can put $1k, $10k or $20k into a project. They’re a good source of funding for friends and family rounds but need to be made aware of just how risky it is to invest in a startup. Tell them to psychologically kiss their money goodbye.

The Exited SMB Founder - This is somebody who sold their small-to-medium-sized business and now has a lot of money sitting around to invest in other stuff. They’re often good at recognizing business opportunities but lack the background to understand how to do tech valuations and financings. This is the archetype that I find most often balking at $5mm valuations for early stage companies. They’re good investors for traditional businesses, but if you are raising on a tech multiple and trying to build a $400mm, $500mm, or $1b company someday, you’ll probably have to educate them on how venture financing works. They may not understand that even with a $75,000 investment, they will only get a few percentage points in the company.

The Real Estate Investor - These people are used to plowing a ton of debt into properties and getting cashflow out. They like numbers, which early stage technology companies often lack. Also good for Friends and Family rounds. Otherwise, they tend to take more time than they are worth.

The Private Equity Man - These people get how tech financing works, but they’ll look to invest to control a company. If they don’t buy a controlling-stake outright, they’ll come in to do so down the line. This is a big bucket but if the company can help them with other companies in their portfolio, they’ll work as strategic investors.

The “Family Office Manager” - There are two types of people who manage money for wealthy people. There are family office managers and then there are “family office managers.” Family office managers manage money for one or a handful of very, very wealthy families (think billionaires and centi-millionaires). “Family office managers” manage money for high-income families, like doctors and lawyers. Their MO is “Don’t Lose Money.”

OLD Money - This is the money from a century or two ago. In Pittsburgh, for example, this is the Hillman family office (an old industrial-era family that owned coal mines). In New York this could be Rockefeller money; in Charleston it would be plantation-owner money. This is where you find real family office managers — but they’re also usually already allocated into major Silicon Valley investment firms and hard to change their ways.

The Public Servant - This is somebody who runs a community-focused incubator or accelerator. They aren’t quite a VC because they aren’t raising money from investors who are looking to beat the market (they usually have money allocated from the state). But if you have a compelling economic development angle or you have a politically palatable story as a founder, they’re worth a conversation.

Compare this against what you might find in a region with a few recent major tech exits:

The (Recently) Exited Tech Founder - In many cases, this is your best-case angel investor. This person has run a venture-backed company and has taken it from beginning (or whenever they took over) to sale or IPO. They can introduce you to investors, they have friends who got wealthy along the way, and they know how the ecosystem works. I want to emphasize “RECENTLY” exited here. I know a lot of tech founders who ran companies in the 80s who are less helpful than SMB owners or Lawyers or Doctors as angels. Tech expectations and ecosystems develop quickly. Uber didn’t even exist a decade ago. Y Combinator is still relatively young. You want to make sure these people have actually faced marketplace conditions recently. The more recently they exited, the more helpful they tend to be (generally).

The Xoogler - Major tech companies like FAANG pay well and a lot of their employees go off to start their own companies someday. Others decide to leave and run their own business and maybe do some angel investing on the side. Former tech employees can be a good source for larger Friends and Family rounds, especially if they stuck around long enough for shares to vest.

The VC - Obviously VCs are more common in tech ecosystems that have had recent exits. After a major (e.g., $1b+) exit, you’ll see some former execs at the company set up their own funds, funds from other tech hubs set up satellite offices, and a general uptick in interest from VCs. VCs are a good source of early stage funding if 1) their fund does that stage funding; and 2) you know you want to pursue a venture-scalable route with your business (more on that in a future essay). Just make sure they actually have money they can invest; VCs have to fundraise just like startups do and some (less-than-ethical) VCs will commit to invest in companies before they actually have the money from their own investors.

The Professional Angel Investor - This is usually an exited founder or Xoogler or burnt-out VC who decided that they’d rather write smaller checks and have full control over whether or not they make investments. They can be helpful; you’ll just want to do diligence on them just as an investor may do diligence on you.

One way that I’ve heard the distinction between tech hub and non-tech hub investors described is “smart money vs. dumb money.”

I don’t like this distinction. Not only is it condescending and assumes far too much about tech hub investors as a general class, it gives people the impression that investors can (or should!) be smart about your industry. Your job at the earliest stages as a founder is to educate and coach your investor along the way in your industry; your investor’s job is to support you and your team and make sure that you are set up for your next round of financing.

A colleague describes early stage investing as “reverse advanced tutoring.” Investors get paid to be taught about technology and industries. Then they make pattern-recognition-based decisions about whether or not to invest.

A better way to think about investors is as “fragile” or “robust” or “antifragile.”

Fragile investors will lose their minds if they make an investment that looks like it will do poorly. These people haven’t done a lot of investing before and they don’t understand the risk:return profile of an early stage investment.

Robust investors can withstand some losses, but they won’t necessarily get better at investing as they face more volatility (positive or negative). They’re usually fine investors to work with but more experience doesn’t necessarily result in better help when working with them.

Antifragile investors are actually more helpful as they face more volatility. They’ll amend their documents to reflect changes in the marketplace. They’ll be able to tell you whether you should go for a seed+ or a Series A round based on current market conditions. They’ll be able to help you with more hiring needs and point you to their own LPs or friends who can also invest.

This is a better framework for thinking of potential investors.

How can non-tech hubs develop better investor climates?

So if you’re in a community or you’re a founder or you’re an investor in a non-tech hub, what can be done to seed the ecosystem for antifragile investors?

The best thing for any ecosystem is a $1b+ venture-backed exit. That leads early employees and founders to go start new companies and to go do angel investment and go become VCs.

But without one of those, what can be done?

One move is to get more people with the “right” backgrounds into investing. Your tech investor scene shouldn’t be a bunch of MBAs who have never worked at a startup. It shouldn’t be lawyers who got tired of being lawyers so they went and started doing “tech investing.” And it shouldn’t be people who haven’t run companies for 30 years.

These people are fine to have in the ecosystem, but they should play roles as Friends and Family round funders, university administrators, and program officers. You want people doing tech investment who know what SAFEs are, can tell you why a firm may prefer a convertible note, has a sense of what the current range of a pre-seed or seed round looks like for different sectors, and can smell charlatans from a mile away.

Your tech investors should have a sense of what the tech ecosystem both locally and nationally looks like. If you’re in a non-tech hub, your companies are going to have to go to New York City or San Francisco to raise funding eventually. So you’ll want them to be prepared for what a competitive funding round looks like there. If your local Series A funding is a $1mm round when San Francisco’s is a $15mm round, eyebrows will be raised when you go to Series A funds asking for $1mm.

You can get these people into investing by making it clear that you don’t need to have a lot of money to start angel investing. I’ve seen cap tables with $1k checks on them. It doesn’t have to be a full-time job for those locally working at FAANG companies or as exited founders.

Another way to get these people with the right backgrounds in is to engage the local startup ecosystem with Boomerang tech workers. People who want to start families can’t get out of San Francisco quickly enough and they want to go to places like Denver and Austin and Pittsburgh and Kansas City so that they can own a home and start a family. Pull them into the ecosystem and get them working with local startups. Nudge out the MBA students who go to work with startups because they think it sounds fun but who wouldn’t be able to find their ways out of an AWS container.

Another option is education. A lot of economic development initiatives in non-tech hubs include bringing in investors from New York City and San Francisco to visit the hub and see what’s going on. “Look at all the tech we have!” the county employees tell the investors. “Please, come invest here!”

That’s all fine and good, but if you have money in the ecosystem, why not send your local monied people to tech hubs to learn what current investment standards are? Put together a trip of high net worth individuals, the local angel network, and people doing Friends and Family investing, put them on a plane to San Francisco, and have them meet with early stage funds who could use their help as scouts.

For the early stage funds, they get the benefit of growing their deal flow and using local knowledge to get into promising companies early. For the local investors, they get the benefit of knowing how to actually invest in 2019 so that promising startups don’t completely leave the local ecosystem to go raise money in larger cities. It’s a win-win.

But at the end of the day, the most important factor is the founder ecosystem. Every non-tech hub wants more investors. Money is fuel for promising ideas. But if you don’t have founders who are willing to make the bet on themselves and their ideas that they can be $1b+ opportunities, you won’t get investor money to follow. Creating founders is a function of having ambitious, smart people in one place and giving them the time and freedom to tinker and explore ideas.

I’m optimistic about non-tech hubs in cultivating new founders, especially given how much cheaper these cities are than tech hubs. The most difficult factor is creating a culture of healthy ambition that lauds and supports people who want to pursue massive opportunities.

How Changing the World Ends Up Turning Your Local Community Into a Mess

“What do people in San Francisco do for status?”

My colleague Michael was enthralled by the question. We had spent the evening discussing what makes San Francisco so dysfunctional as a city. It’s a place with so many smart, ambitious people but also a place with more heroin addicts than high school students (real fact).

I nursed my beer and looked out over Laguna Beach as I mulled on the question. I hope Michael will write on the status question at some point. He’s on to something with his answer to it.

“I think status there follows a lot of what happens on a global scale. So to have status in San Francisco is to do something globally,” I pondered. “I remembered seeing a tweet a few weeks ago related to this that had me thinking. It essentially went like this: people in SF are focused on impact at scale. People in New York are focused on impact locally. This actually makes things better in NYC than SF because in pursuit of status, people make things better around them. New York is all the better for this class.”

(I dug up the original tweet by @zck here:

I think this is essentially correct and explains a lot of the mess that is San Francisco or Los Angeles’ politics and civic institutions. All of the most competent and driven people in the cities (tech for SF, media and consumer tech for LA) are focused on global-scale impact and end up disregarding the local.

But when we disregard the local, the local doesn’t disappear. It just gets worse. And the obligations towards the local end up falling by the wayside or get taken over by the worst of all people.

This is why nothing can get built in San Francisco. It’s that the people who are so busy working on “changing the world” don’t go and participate in their neighborhood politics. So the people who do go participate in neighborhood politics are the worst possible people: NIMBY Boomers who haven’t worked a job in 10 years and whose top priority is making sure their property values don’t drop. They block every bit of housing however they can — including by declaring laundromats to be historical buildings (again, real thing).

San Francisco’s development problems are largely institutional. People follow incentives and the incentives are set by their political and social institutions.

But there are both formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include law and statute; political and legal; rules and codes. Informal institutions are trickier. These include the expectations of a community; the expectations you enforce against yourself; and culture.

Informal institutions are largely (though not entirely) spontaneous orders. This is a Hayekian concept meaning that they are the products of human action but not of human design. No one person sits down and decides, “yes! I will make it honorable to focus on ‘changing the world’ and cute to focus on making your city or neighborhood better first!” That just becomes the norm based on many dozens or hundreds or thousands or millions of interactions between people acting under the incentives they face on a daily basis.

But some informal institutions are influenced by formalized institutions. Ethical standards of obligation are great examples here. Ethical standards of obligation are largely influenced by culture but that culture can be formed by its foundational religious institutions (or those religious institutions can be influenced by the culture, just look at the Episcopalian Church).

_________

Almost all ethical frameworks start with the assumption that we have moral obligations. We have obligations to other people to act, to help them, and to prioritize helping them over non-moral actions (like going to the dry cleaners). Most questions in moral philosophy come from conflicts of obligation. Do you help X or Y? Do you use resources now or later? Do you lie to the ax murderer or Nazi at the door or do you tell the truth? Do you focus on what you can control near to you or what’s far away from you?

We can ask a similar question regarding taking care of your community. With the limited resources you have, should you focus your time and energy on trying to make the whole world a better place or should you focus on making your local community a better place?

Ethical frameworks influenced by the Judeo-Christian framework say you should focus on what’s nearest to you first. You first must take the log out of your own eye before you ask somebody else to take the splinter out of his. You first must care for yourself and your family before trying to change the world.

This is intuitive to anybody who has spent a significant amount of time in a place of worship. Not long after this conversation in Laguna Beach, the homily at my local parish was in fact on this topic. “We wouldn’t think highly of somebody who puts his family in the poor house in order to do charity,” the priest told us. “Likewise, we wouldn’t think highly of somebody who does no charity with those who are in need of it. We must take care of those nearest us. Then we must help those in need of help as we can.”

Indeed, this is a thoroughly culturally conservative framework to work off of. Jonathan Haidt’s moral emotions research backs this up, as people who identify as more politically conservative tend to prioritize the local over the global (think of people saying we should take care of our own before we worry about what’s going on overseas or at the border).

But there’s no need for this to be an inherently political way of thinking about moral obligation. It’s one that logically follows from a position of humility and limited knowledge (core precepts of Judeo-Christian religion). You have limited information, limited ability to make an impact, and limited resources. You should spend it on yourself and that which is nearest to you first and foremost.

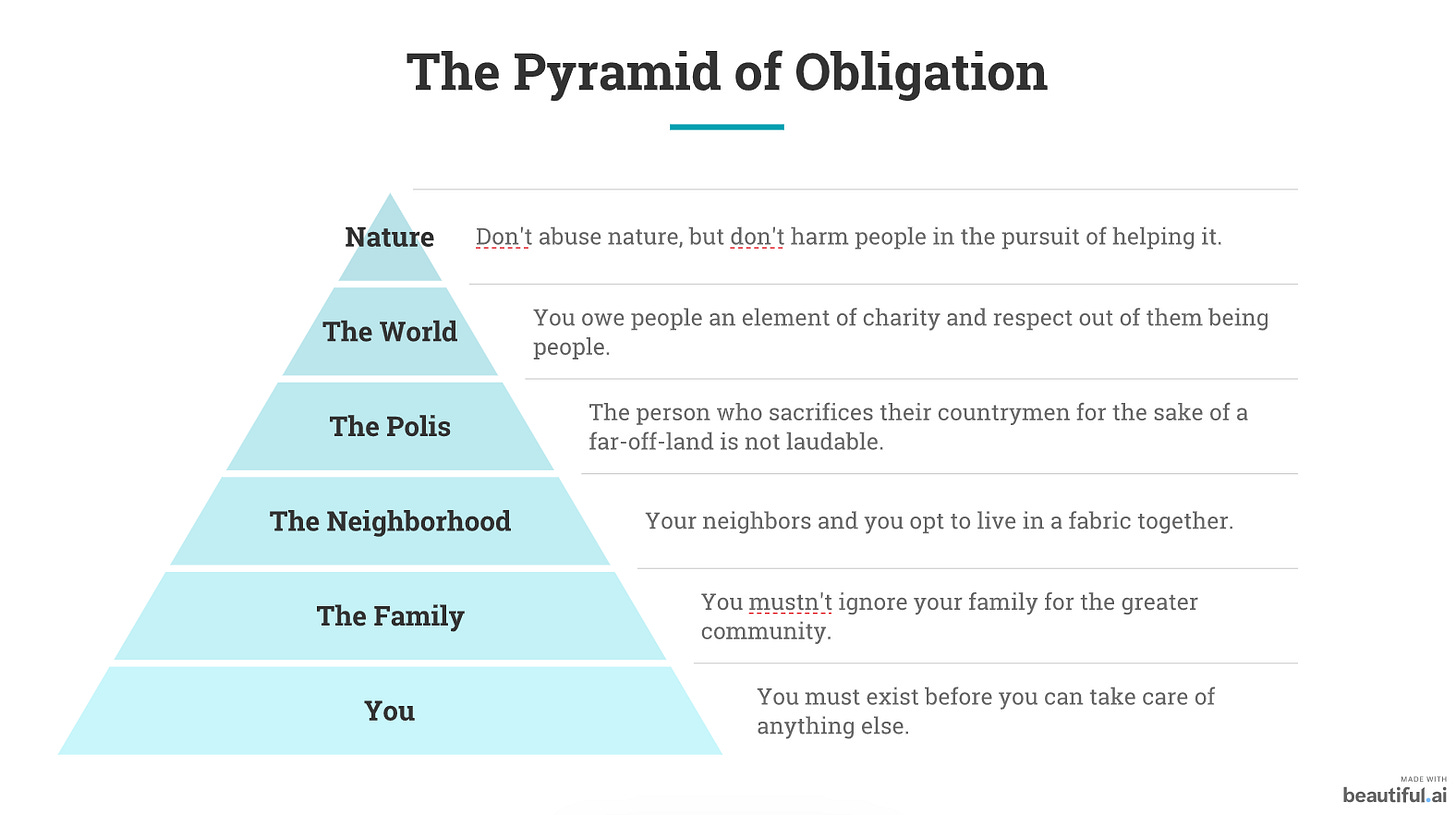

Philosophers like Peter Singer and Elizabeth Anscombe have illustrated this concept with concentric circles, with that which is closest to you in the center and the whole entirety of creation at the furthest circle. I’d rather think of it as a pyramid like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs — that which is at the bottom must logically come before that which is at the top. You cannot achieve what is at the top without that which precedes it. And importantly (as we’ll see below), that which is at the bottom of the pyramid works as a foundation of that which comes later.

At the very bottom of the pyramid is the individual. You must exist and take care of yourself in order to shepherd and take care of your own family. Then comes your family, which works as a foundation for the neighborhood. Your neighborhood makes up the polis (or the political community with which you identify and in which you live). And the world is made of political communities. Finally, taking care of nature comes only after you’ve taken care of your obligations to the world, the polis, the neighborhood, the family, and yourself.

Of course this doesn’t mean don’t help nature, or don’t help your neighbors. It just means “help them once you have fulfilled your obligations that come first.” Sacrificing your family for your neighbors is considered improper.

(Of course there’s an exception for martyrdom. Sacrificing yourself for your family is considered laudable for some but that’s an edge case.)

This pyramid shouldn’t be debatable. In this framework, what is up for debate isn’t the order of obligation but the extent to which one must fulfill obligation before moving to later stages of the pyramid.

Contrast this with the pyramid that extends from a value framework that negates either the need for community obligations or an objective good (i.e., religion provides an objective good against which people can measure obligations). In this void, we have nothing to judge whether or not an action is good or bad besides how it either affects us or is interpreted by us.

So what follows isn’t a pyramid but rather a funnel, similar to an inverted version of the pyramid of obligation.

In the funnel, we start with the biggest impact we can make and good travels down the funnel, eventually hitting you, the individual.

“We all live in the world, so making the world better surely makes everybody else better, right? So let’s focus our efforts on making the world better.”

“Once we make the world better, then we can focus on the good of making the neighborhood better, our family better, and all of that will result in my life being better.”

(I leave out the polis here because in reality, I find few who subscribe to the funnel believing in any value of the polis. But if you disagree with me, you would insert the polis above the Neighborhood but below the World.)

You can think of the funnel as applying to the world-dreaming founder who wants to start a company that will change the world. He’ll move across the country to do it and say “goodbye!” to all of his local associations so that he can do this.

Or you can think of the careerist professional who focuses first on making a lot of money in their career, justifying it to themselves that once they do that, then they’ll be able to take care of their neighborhood, and once they’re in a good neighborhood, then they can focus on a family.*

But the issue with any funnel is that the funnel only works if the substance (in this case, good-ness) actually flows down the funnel.

If that substance gets stuck at the top of the funnel, it doesn’t reach the bottom. And the whole goal of the funnel is to get to the bottom of the funnel.

For a whole slew of reasons, it’s hard to make an impact at the top level (“Nature” or “The World) in a way that allows you to really see good on the local level. We’re creatures of limited intellect and information. Just because we think — or even know! — that big-level planning will work out well in one area doesn’t mean that the good from that big-level planning will manifest as good when it gets closer to the neighborhood or to the family or to us.

This goes both for policy (e.g., Hayekian knowledge problems) and for life. We’re bad at knowing what we’ll want. We may think we know what we’ll want in 15 years — and indeed, we should have plans! — but we need to think about those 15 years based on fundamentals that we want and do not want in our lives.

If your ability to live as a good neighbor, community member, or parent is contingent on changing the world, not only will your neighborhood, community, and family suffer while it waits for you, you may never actually get to your goal of being good.

Think bottom-up, not top-down.

* So the obvious question here is, does the funnel usurping the pyramid follow from a lack of religion? That’s beyond the scope of this essay but it would not surprise me. A cursory look at statistics shows the Bay Area to be largely irreligious (and I would expect those numbers to be even lower among the tech twitterati — e.g., 16% Catholic in SF comes from the city having a large Hispanic population), even compared to the greater NYC area).

Recommended Product

A lot of the people I talk to want to start a company someday. Whether that’s a startup that they think can impact a ton of people or a side-business that provides a reliable income.

The question they often get stuck on is, “what should I start?”

But not all business owners are the people who started the business. Not all founders are the original founders (you can re-launch a business, after all).

But the idea of buying a business is imposing and confusing to most people. How do you choose the right company? What are the right documents? How can you find financing?

Micro-Aquisitions is a comprehensive course on how you can buy, grow, and sell your own small business, even if you don’t have a lot of money to do so right now. I’ve personally taken the course and have found it both enjoyable and insightful.

The creator updates the course regularly and includes:

Email scripts for outreach.

Lists of places to find and buy businesses.

Case studies on negotiations and acquisitions.

Spreadsheet templates for EBITDA analysis.

Recommended books and further reading.

Here’s the thing about online courses: a lot of people charge way too much for them. You’ll find courses online that are $1k, 2k, or even 3k that really could be a few hundred dollars’ worth in book purchases.

I’ll never recommend those.

This course is only $150 — a steal when compared to the price at which it could be priced.

(This is not an advertisement. I just enjoy this course that much and have seen it work for others.)

Fascinating Job

At first glance this just looks like your run-of-the-mill mobile developer job. I’ve included it here because the product you would work on is one of my favorites I’ve come across recently: Cabin.

I’m the child of two airline employees, so transportation is inherently fascinating to me. Particularly fascinating is the idea of opportunity cost in transportation. Why should you have to waste so much time just to travel? Even if you’re flying in first class, there are still hours of wasted time settling in to your seat, going through security, waiting for the plane to take off, and dealing with the cognitive stresses of travel.

Cabin tackles this problem by trying to make the time in transit less stressful and more useful to the traveler. Their first product does this by letting the traveler use time they’d spend sleeping both sleeping and traveling.

Their CEO has a few great essays on time travel here and here.

Who I’m Following

@RyanCKulp, who created the Micro-Aquisitions course above and continues to be one of my favorite follows. Ryan doesn’t really virtue signal to anybody because he doesn’t have anybody to impress.

What I’m Reading

Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber, by Mike Isaac.

Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (second time reading this — excellent book with a high re-readability factor)

“What the Downturn Will Probably Look Like in SaaS” by Jason Lemkin

(Plus essays included in 00.1 - Prologue)

Until the next issue —

Zak

Let me know what you liked most from this issue in the comments below or by emailing me directly.

This is a limited-edition free issue. If you are a free subscriber, this is a sample of what you’ll get regularly in your inbox if you become a monthly subscriber. If you have questions, please email me!